Research links plasticizer to infertility

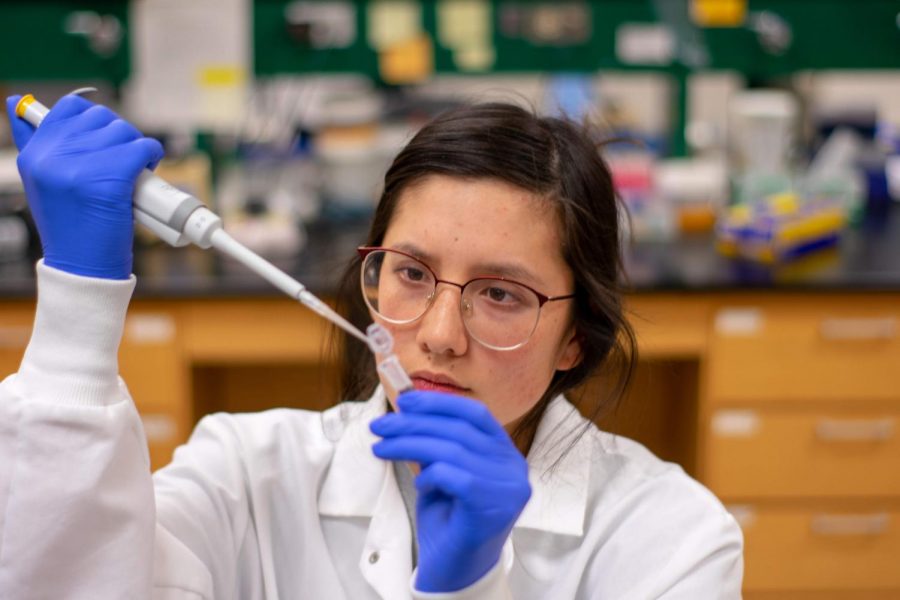

Katie Chiang works in her lab at the Veterinary Medicine Basic Sciences Building in Urbana on Tuesday. She’s been involved with research at the College of Veterinary Medicine since 2013.

February 25, 2019

Researchers at the University have found feeding mice doses of phthalates, found in plastics, decreases fertility in female mice for up to nine months afterward.

Jodi Flaws, professor in Veterinary Medicine, said people have to care about fertility in female mice because we are exposed to these compounds every day.

“They are in a lot of different products, and phthalates, the main category of the chemical, are in a lot of care products such as shampoo, lotion, makeup (and) nail polish,” Flaws said. “The level in women tends to be higher than in men. The reason is because women are more likely to use personal care products than men.”

Katie Chiang, doctoral student in comparative bioscience and co-author of the study, said the phthalates research is a continuity of a previous study which showed 10 days of exposure of a very common plasticizer called di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate.

“My studies aim at the following up on that study to see how 10 days of exposures to this plasticizer affects female fertility over the life of these females,” Chiang said. “In addition, I wanted to test a replacement for DEHP because some products are now removing DEHP and using something else.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The team is aware of more studies they still have to do, but their main focus remains on knowing what this chemical can do in fertility. With funding from the National Institution of Health, the studies on the phthalates are planned to go on for the next several years.

“Katie’s study is almost complete, and hopefully in the next year we will finalize all of those data,” Flaws said. “With the funding, we start examining the mechanism by which the phthalates are causing problems so that if we could better understand the mechanism, we might be able to develop some ways to prevent some of the toxicity.”

Chiang said little research has been done, so she is studying a replacement called diisononyl phthalate, or DiNP.

A substance such as Bisphenol-A contained in some plastic water bottles is usually replaced with an alternative plastic, which is the focus of Chiang’s study.

“I know that I wanted to bring in the DiNP because I am really interested in regrettable substitution like BPA,” she said. “We are finding that a lot of replacements are worse than BPA.”

In the next couple months, Chiang’s team will collect the exposed mice, have their tissue sampled and look at their hormone levels.

Chiang has been following female mice out as far as 15 months after their original dosing with no exposure. Chiang has been working on the study since August 2016 but has been writing the proposal since spring of 2016. Though her main focus has to do with understanding how these phthalates act on decreasing fertility, she said it’s hard to look at the future and know what it is as you might be looking on something specific and end up discovering other paths.

“We cannot draw that direct link that ‘this’ will cause ‘this’ in humans, but we chose mice to work with as a transnational model for humans as their ovaries have very similarity with humans,” Chiang said. “We know that these affect mice. We know that their ovaries are similar to humans, so it’s something to consider.”

Flaws said the researchers came up with this conclusion after seeing similar scientific data.

“There are some human studies where they look at people that are exposed to phthalates and they do see in those studies some association with reduced fertility and abnormal hormone level,” Flaws said.

Chiang plans to keep writing papers for every month the mice are dosed. So far, she only presented data for zero, three and six-month post-dosing even though the mice are already going to their 15th month.

This study is similar to research Flaws did in 2015 where she focused on pregnancy and exposure to phthalates and what it does to the offspring.

“We know that pregnant women are exposed, but also adult women are exposed,” Flaws said. “In this study, we are looking at a short-term exposure and the consequences of that for the reproductive lifespan. Where in a previous study we had a bit longer exposure during pregnancy and not exposure once the pups were born, kind of looking at what that did to the development of offspring.”