Slim pickings with sky-high prices

February 22, 2023

During the apartment search, choosing a home away from home on campus is a complicated decision, with options ranging from century-old houses on cobblestone paths in historic Urbana to the luxury high-rise apartment buildings on Green Street.

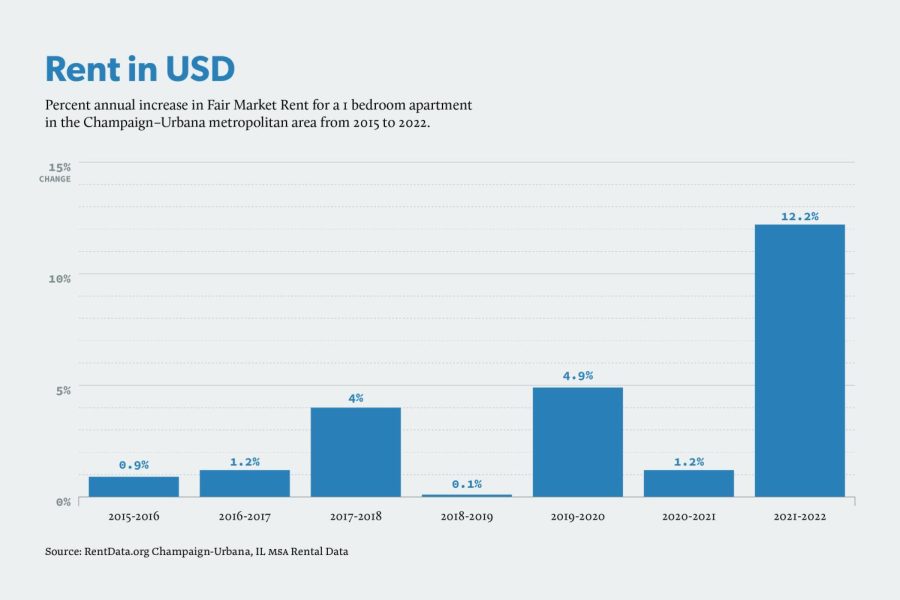

According to data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Fair Market Rent, or FMR, for a one-bedroom apartment in the Champaign-Urbana metro area grew from $739 to $829 between 2021 and 2022 — a 12% increase. FMR is a representative statistic for rent established by the HUD and calculated by finding the 40th percentile of rent costs in an area.

In the opinion of Perla De La Torre, sophomore in AHS, the recent increase in rent is “unreasonable.”

“Rent has gone up a lot at my friend’s building,” De La Torre said. “This year, her rent is $600, but … it’s $750 for next year. Still, her building sold out pretty quickly.”

These rent increases don’t just impact potential residents, but also returning renters.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

According to Dr. David Albouy, professor in LAS, the recent hike in rent costs is happening in direct response to the market.

“There’s been a growing affordability crisis in the country at large since about 2001 … across a lot of geographies, there’s a lack of new housing supply in places that people want,” Albouy said. “Demand moves around, and supply has to keep up.”

The increase in rent on campus has not gone unnoticed by students. Many students are worried that they will be unable to find housing for a reasonable price, including Lizela Figueroa, freshman in LAS.

“All of the good apartments close to campus are really expensive,” Figueroa said. “I was only here for a month when all of my friends were saying that I had to pick an apartment right away or else they would all be rented out.”

According to Brooke Beyer, sophomore in Education, students should consider starting the apartment search in the fall before your current lease is up.

“The best time to look for an apartment is during the fall of the previous year, I would say,” Beyer said. “The apartments go fast.”

Kevin Lu, junior in Business, thinks this timeline puts pressure on apartment residents to renew their leases far too early in the year.

“They want us to look for apartments ridiculously early in the semester,” Lu said. “The problem with this approach is that they make you decide before you’re accustomed. You have to re-sign somewhere before you know whether you like it, or even who you’re going to want to live with next year.”

Lu went on to say that leasing companies artificially hike rent costs because students continue to need campus housing regardless of the price tag.

“I think the leasing companies take advantage of students needing to live on campus,” Lu said. “Honestly, they charge you whatever they want to charge you because you have to pay for it if you want to live on campus.”

The Daily Illini reached out to several leasing companies and all declined to comment or did not respond.

According to Albouy, Central Illinois is generally one of the most affordable places to live, but the University’s campus is an exception.

“We have lots of land around here,” Albouy said. “Some of the cheapest places in the country are about a half an hour of driving away. You can buy a mansion in Danville for a bargain.”

Although living further from campus and commuting to class using public transportation is often a cheaper option than looking for an apartment within walking distance, Albouy said that he understands those who choose to live closer to the action.

“I think that there’s a certain beauty in campus living; being close to one another, your neighbors being related to the campus as well,” Albouy said. “But there’s a little bit of student segregation that way, too. Lower-income students might be forced to self-segregate from other people.”

As new amenity-packed apartment buildings continue to replace older, more affordable units on college campuses across the country, some rush to blame the buildings’ developers for increases in rents across the board. According to Albouy, this is a mistake.

“We typically think rental markets are fairly competitive, and so they’re driven by a lot of supply and demand,” Albouy said. “So, blaming a few landlords for rising rent is a bit tenuous, because one big building with 500 or 700 residents is not moving the market.”

Albouy also said increased demand for luxury housing is the reason for its continued development.

“The fact that the luxury buildings are selling out is a sign that there’s a shortage of these kinds of places near the campus,” Albouy said. “You see these huge new buildings and ask, ‘How could there be a shortage?’ I mean, it’s what people want. Some students want to live close, and they don’t want to live in an old apartment.”

An upgraded one-bedroom unit with a private hot tub at The Hub, a luxury student apartment building, rents for over $2000, not including utilities. This floor plan sold out relatively early in the leasing cycle.

Albouy said that a gradual, generational shift in expectations for standards of living is a potential reason for luxury buildings’ popularity. To illustrate this, he recalled his father’s “waxing nostalgia” of a Paris apartment furnished with a cinder block bookshelf.

“Luxury student housing, to me, should be an oxymoron,” Albouy said. “I think here what we’re seeing is a manifestation of inequality at large, and it’s playing itself out in the housing market. Some parents have no problem putting their kids in luxury housing.”

From an economic standpoint, Albouy said that rising prices are indicative of a positive trend in Champaign-Urbana. Sagging rents in places like Decatur and Danville indicate a lack of demand to live there, according to Albouy.

“A rise in rents is kind of a sign of (economic) health in a long-term sense,” Albouy said. “It’s a case of more people and a similar amount of housing.”