Bias in health care affects women, new study finds

March 7, 2023

A new study from a University professor and a group of graduate students examined how women feel as if they aren’t taken seriously by physicians.

Charee Thompson, professor in LAS, alongside Sara Babu and Shana Makos, graduate students studying communication, studied the experiences of female patients who said they felt dismissed by physicians.

“Trust the fact that if you feel like something is wrong with your body, there probably is,” Babu said.

Researchers said their experiences can be summarized as communicative disenfranchisement.

Communicative disenfranchisement is defined by Elizabeth Hintz from the University of Connecticut as “disempowering talk which results in an individual or group’s diminished capacity to participate meaningfully in society through effects on agency, perceived credibility, legitimacy and/or rights and privileges.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

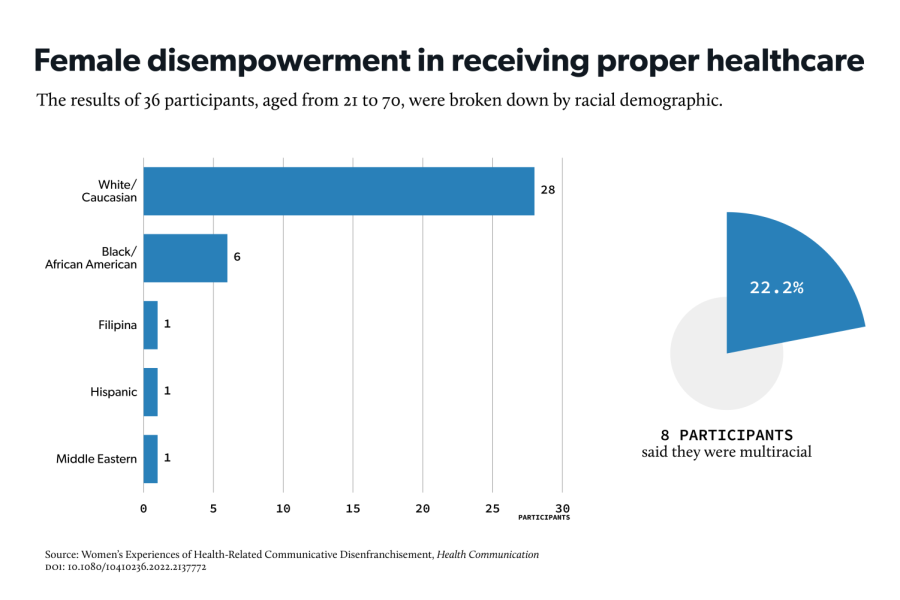

The study observed 36 women in the U.S. with chronic pain disorders ranging from ages from 21 to 70. Among these disorders were polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis and cancer.

According to participants, many physicians cited mental health issues as the primary cause of their symptoms. Among these were anxiety and major depressive disorder.

“Women responded to disenfranchising talk with silence, and they (reclaimed) their voices by resisting psychogenic explanations for their problems, critiquing women’s health care, asserting their needs and advocating for others,” Thompson said.

Psychogenic refers to a problem that is psychological rather than physical.

According to the study, some participants said they also felt dismissed by family and friends during conversations about their health. Some said the feelings of guilt and shame, much like their long-standing health issues, carried with them for years.

“The intensity and duration of their experiences was surprising, and it shouldn’t have been,” Thompson said.

One participant said she regarded the normalization and dismissal of her pain as “a lifetime” rather than episodes of disappointing interactions.

Monica Mezzich, senior in LAS, who has experienced similar situations, said she felt dismissed by a doctor when attempting to address a recent health issue.

“The doctor talked down to me assuming I didn’t know my body as well as he did. My issues weren’t taken seriously,” she said.

Thompson and Babu said there are strategies to combat disempowering communication between health care professionals and female patients at the individual and systemic level.

Thompson said shifting to a more informed discourse surrounding women’s health in the media and in conversation can also help create systemic change.

She also said female representation in health care can lessen instances of communicative disenfranchisement, especially in female-focused specialties. “We can go with them to appointments where they may be concerned that they may not be seen as a credible witness to their health,” Thompson said.