Looking back: Project 500 in retrospect

In 1968, 565 students from underrepresented minority communities were recruited attend the University of Illinois as part of Project 500. Miscommunication regarding housing for the newly-admitted students led to a protest at the Illini Union — and the arrest of over 200 students.

Photo courtesy of the University Achieves

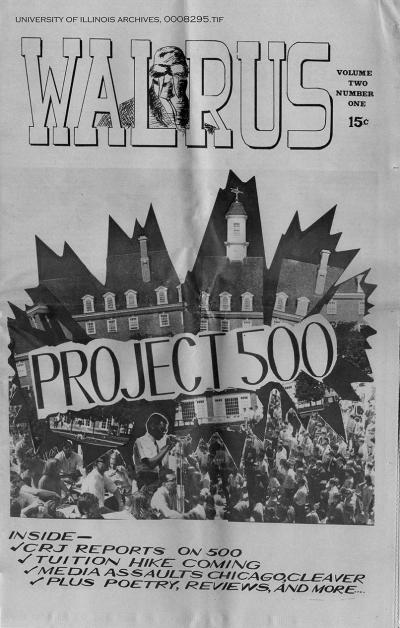

The front cover of “Walrus,” a student-run publication from the ’60s. The Special Educational Opportunities Project, also known as “Project 500,” recruited students from underrepresented populations, and it’s implementation received mixed criticism from the student body.

January 19, 2022

On a cold January night in 1968, students, professors and cameramen packed into the Illini Union. Clouds of smoke filled the air as leaders from the University of Illinois and other institutions debated the problems of the day: The Vietnam War, student liberation and racial equality. Radicals, reactionaries, liberals and conservatives sat wall-to-wall to either partake in or watch the night’s discussion.

The conversation, organized by the University’s Public Broadcasting Laboratory, was nationally broadcast – displaying an instance of ’60s college campus culture. Lit cigarettes, students in suits, sunglasses indoors and a mixture of crew-cuts and shaggy mops – this was the ’60s.

As the conversation swung toward Vietnam, with most students condemning the Nation’s involvement in the war and use of chemical warfare, others felt that problems on campus were being overshadowed. One speaker chimed in: “What about the psychological and moral napalm the white students are dropping on Black students. Where has been the student movement across the nation to protest this?”

As the debate progressed, tensions flared. Feeling unheard at the debate – and at the University writ large – the University’s Black students staged a walkout, refusing to participate in a conversation dominated by institutional voices.

Mike Rossman, a leader from UC Berkeley invited to speak at the debate, noted “the fact this discussion hasn’t gotten anywhere is a testament to how deep the problem is. The fact of the matter is quite clearly that this institution, which is the major institution which shapes white America and Black America has shown itself absolutely incapable of dealing with critical social problems we have today.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

There was, and still is, a problem on campus. How does a predominantly white institution of the state work to ensure equality in both opportunities and material conditions for all its students?

The University’s answer to this problem was the Special Educational Opportunities Project – colloquially known as “Project 500.” Recruit students from underserved populations at a higher rate than previous and foster diversity on campus. Five hundred and sixty-five students from underrepresented minority groups were recruited for the project to attend the University in the fall of 1968, and the beginning of that semester was filled with hope for a more diverse campus.

Less than a month later, miscommunication between University administration and students led to a protest at the Illini Union. Two hundred and forty-eight students were arrested, the majority being freshmen recruited as part of Project 500. What was intended to be an institutional attempt to reckon with the institution’s own lack of diversity was nearly over before it began, placing the very students it sought to protect in harm’s way and highlighting the flaws of an institutional attempt to solve a systemic problem.

Diversity on campus pre-1968

The story of the University – as with many of the nation’s public institutions – and its surrounding community can’t be told without mentioning discrimination and exclusion. As documented in professor of education Joy Ann Williamson’s book “Black Power on Campus: The University of Illinois, 1965-1975s,” Champaign-Urbana restaurants, barbershops and theaters remained segregated until the mid-1960s, and University Housing refused to house Black students until 1945.

The University never refused admittance due to race, yet it wasn’t until 1887 – 20 years after the University’s inception – that the first Black student, Jonathan Rogan, was admitted. Rogan never completed his degree, and it took until 1900 for William Walter Smith to become the first Black graduate. Six years later, Maudelle Brown Bousfield became the first Black woman to graduate from the University, earning degrees in astronomy and mathematics.

Detailed records regarding the University’s racial demographics were not kept prior to 1968. Albert Lee, a clerk in the University President’s office – known as the first unofficial “Black Dean of Students” due to his involvement with the University’s Black community during the early 20th century – kept unofficial tallies of Black students and graduates. In 1940, Lee published “Data Concerning Negro Students at the State University,” a report detailing the history of the University’s Black students.

In the fall of 1925, the first year recorded by Lee, 68 Black students were enrolled at the University. The number fluctuated year by year, and by the fall of 1930, 92 Black students were enrolled at the University – less than 1% of the University’s 12,861 students.

Little progress in increasing campus diversity was made throughout the ’30s and ’40s. Prior to 1968, the University only kept decennial records of student enrollment with no official records of racial demographics. However, comparing Lee’s records of Black student enrollment to the University’s records, the ’40’s weren’t any different than previous decades. Just over 1% of the University’s student body was Black at the turn of the decade.

Lee retired in 1947 having served under multiple University presidents, and along with his departure went his consistent documentation of campus diversity. Twenty years later, near the end of the Civil Rights movement and the heyday of the ’60s, only 372 of the University’s 30,400 students were Black – barely over 1% – according to Project 500 records. As post-war economic security brought unseen stability to America’s middle class and more people than ever had been afforded the opportunity to attend college, Black enrollment remained stagnant.

The Project

Students and Illinois residents took note of the University’s dismal diversity record and began calling for efforts to increase diversity and recruit from underserved populations.

The University’s response to these calls was the Special Opportunities Education Project – an initiative to recruit students from underrepresented communities who may not have had the opportunity to attend otherwise. David Eisenman, an assistant dean of students who was instrumental in establishing the project, noted in communications that these students would be an expansion of the incoming class.

The University admitted 565 new Black and Latino students in the fall of 1968. This year is also the first year with detailed racial data accessible from the University’s Division of Management Information. When accounting for Project 500’s new students, 2.67% of Illinois students self-identified as African American – 852 of the University’s 31,843 students.

While the group of newly-admitted students diversified an overwhelmingly white institution, Illinois’ campus was still far from resembling Illinois as a state. According to census data, in 1968, roughly 11% of the U.S. population self-identified as African American. In Illinois, that proportion was closer to 13%.

Dr. Sundiata Keita Cha-Jua, professor in LAS at the University who studies Black racial formation and Radical Black Intellectual Traditions, notes that Project 500 was not unique to Illinois. Instead, the project was indicative of nationwide attempts at the university administrative level to respond to social movements such as the Black Power movement.

“The University presents (Project 500) as a unique phenomena that is a representation of their particular brand of liberalism, which of course is a myth,” Cha-Jua said. “If we come to understand these phenomena as nationally driven by the Black liberation movement, these are responses to and concessions to the Black liberation movement, in both its Civil Rights and its Black Power waves.”

Cha-Jua also emphasized the role Black activists had in influencing the University’s efforts to increase diversity, noting that university administrations rarely act without outside pressures.

“What we have to understand is that these institutions do not act on the basis of their own initiative to resolve issues of racial oppression,” Cha-Jua said. “They resolve waves of Black struggle, and when those struggles are high and effective, the institutions respond. When those struggles wax and wane, the institutional response waxes and wanes.”

This increase in campus diversity seen in the fall of 1968 was not solely due to the University’s recruitment efforts. The assissanation of Martin Luther King Jr. in April of that year sparked a renewed emphasis on Black education and spurred record numbers of enrollment for Black students. According to Cha-Jua, In the fall of 1967, approximately 8,000 Black students attended predominantly white institutions nationwide. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. By the subsequent fall semester, over 80,000 Black students were enrolled at predominantly white institutions.

While Project 500’s recruitment efforts succeeded in increasing diversity on campus, logistical elements were insufficiently planned and poorly carried out. Frustrations regarding these overlooks and miscommunication from University administration boiled over in September 1968, shortly after the newly-admitted students arrived on campus.

The Protest

The 565 newly-admitted students arrived on campus prior to the start of the academic year to attend workshops in conjunction with typical welcome-week activities to familiarize themselves with the campus. For the duration of these workshops, the new students were temporarily housed in Illinois Street Residence Halls.

According to communications from Chancellor Jack Peltason’s office, when the week of workshops came to an end on Sept. 8, 1968, the students were directed to vacate ISR so students with previously signed housing contracts could move in. Some students found their newly-assigned dormitories to be less-satisfactory than their temporary housing at ISR. Others were left without housing altogether and forced to relocate to “temporary quarters” until new housing arrangements could be made. There was little word on the timeline of these new arrangements.

The following day, a mass of students – many of whom being newly-admitted Project 500 recruits – occupied the Illini Union to showcase their frustrations at a lack of foresight. According to a Student Senate report published in the subsequent days, David Addison, president of the Black Student Association, led an occupation of the Illini Union’s south porch with the demand that the housing division decision be reviewed by the Chancellor.

It began to rain, and the students moved inside the Union. At 11 p.m., Dean of Students Stanton Millet, along with various other administrators from University Housing, met with leaders from the Black Student Association in the BSA’s office located on the second floor of the Union. Their conversation was unproductive, and no change in University Housing’s plans was forthcoming.

Millet went downstairs to communicate with the protestors.

“Which students are dissatisfied?” Millet asked, according to the Student Senate report.

“If one student is shortchanged, we all are, you will have to deal with us all,” the crowd responded, according to the report.

Millet then said the situation was being worked on but refused to promise any specifics regarding the housing situation. The protest continued, and the Union remained occupied. Leaders from the BSA demanded that Chancellor Peltason be contacted to speak with them by 1 a.m.

The 1 a.m. deadline passed, and according to witness testimony, a small group of approximately 10 individuals began to destroy Illini Union furniture. This furniture included a chandelier and furnishing in two of the Union’s lounges. The vast majority of protestors remained peaceful.

According to the Student Senate report, Peltason was contacted at approximately 2:50 a.m. and communicated that the most important thing to do was to clear the Illini Union to “avoid another Columbia” – referring to student protests at New York’s Columbia University.

In the early hours of the morning, administrators warned that unless the crowd dispersed at once, arrests would be made. Shortly after the warning, approximately 100 police officers from the Champaign, Urbana, University and State police departments entered the Union equipped with riot gear and gas masks.

Two hundred and forty-four individuals were arrested. According to doctoral candidate John Carpenter’s thesis regarding the occupation as well as police reports, 218 of the arrested were new students, three were transfer students, 19 were continuing students and four were not attending the University. Champaign and Urbana local jails were not equipped to detain large numbers of arrestees, and many of those arrested were detained in a makeshift jail located in Memorial Stadium’s West Great Hall.

In a statement released by the Chancellor’s Office, damage to the Illini Union figured around $4,000 – roughly $31,000 today when adjusted for inflation.

The protest and subsequent arrests made headlines across the country, attracting criticism to the University’s decision to use police force to remove students from the Illini Union. Robert Powell, president of the National Students Association – an organization of college and university student governments – wrote an open letter condemning the arrest of the protesters.

“It is unclear to us how students can be guilty of trespassing in their own student Union,” Powell wrote. “Once again, a University administration finds physical force the solution to legitimate student grievances. It seems a sad start for a program conceived in and dedicated to the spirit of non-violent racial progress.”

In Retrospect

When the University celebrated Project 500’s 50th anniversary in 2018, things had changed, while struggles persisted. Diversity increased at the University year by year, and in 2016, the University appointed the first Black chancellor – Robert J. Jones – in the institution’s history.

Yet, the proportion of University’s Black students lags behind the population of the state writ large. At the start of the fall 2021 semester, 3,013 Black students were enrolled at the University, just under 5.4% of the University’s 56,257 student population.

To commemorate the Project’s 50th anniversary, as well as to reflect on the progress made and the progress that has yet to be made, the University held events at the Levis Faculty Center and the Alice Campbell Alumni Center. Alumni who attended the University as part of Project 500 were received at events dedicated to remembering the project.

Jessica Ballard, archivist of Multicultural Collections and Services at the University Archives, created exhibits for these events, as well as for display within the Main Library. While creating these exhibits, Ballard worked with primary documents from the era and conducted interviews with alumni who were part of the project.

Ballard reflected on the University community’s common misconceptions regarding the project.

“I’ve heard some people say that (Project 500) was the first 500 Black students on campus,” Ballard said. “The first Black student enrolled at U of I was in the late 1880s, and the first to graduate was in 1900. I think a lot of people, when they hear Project 500, they definitely think of student activism as well, and that started with the project. There was student activism before, although it increased at the time of the project.”

The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in the early ’60s occupied a space indicative of the land-grant public university of the time – often professing progressive values while lagging behind in setting said values into action. The ’60s were also a time of doubt. College students began to doubt the stories they’ve been told year-in and year-out. Liberation was the name of the game, yet liberation meant two different things for two different groups on campus. For white students, it meant challenging their professors and the rhythm of metro-work-sleep. For Black students, liberation was concrete, to be represented on a predominantly white campus and be afforded opportunities to climb the economic ladder by gaining a largely-inaccessible education.

Project 500 succeeded on some fronts and failed on others. Campus diversity increased, and students from underrepresented communities received opportunities previously unoffered. Yet poor planning and miscommunication on the hands of the University’s administrators placed these students in material harm’s way, and the arrest of non-violent protesters jeopardized their education before it even began.