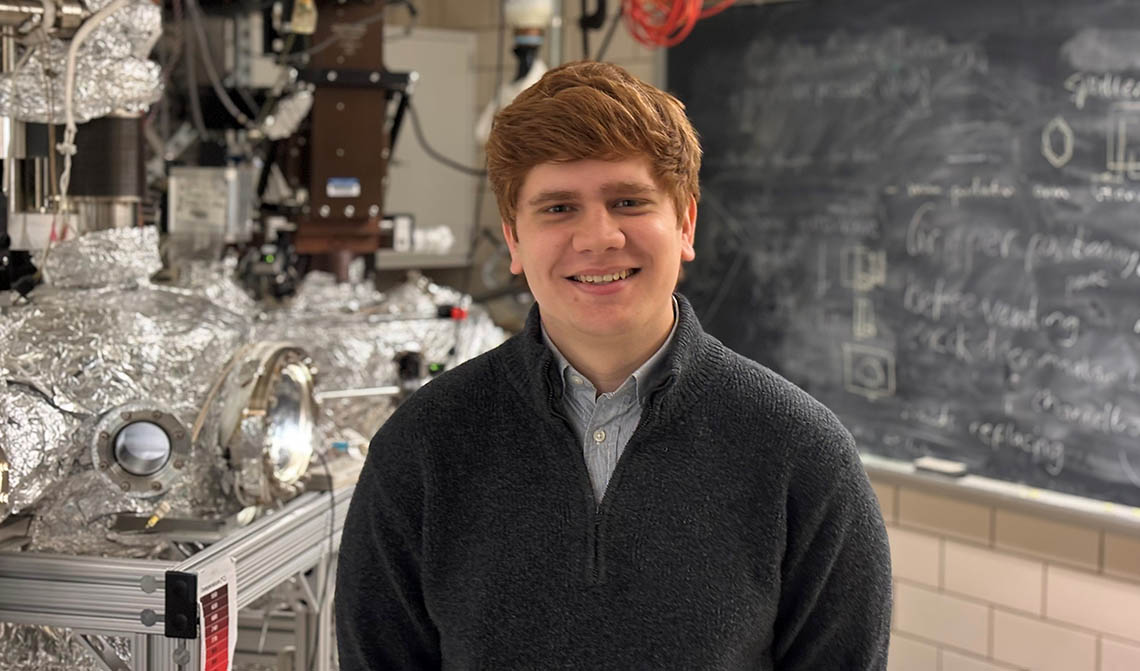

Tony Studer, professor in ACES, received a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to further develop “pop-omics” — his popcorn-based curriculum — last September. The grant provides the funds that make it possible for the pop-omics curriculum to reach K-12 schools.

The pop-omics curriculum is primarily used to teach genomics in the classroom by allowing students to interact with and cross the genetics of different popcorn breeds.

Often nicknamed “the popcorn guy,” Studer travels to K-12 schools to teach students about the genomics of popcorn.

“I’ve learned that it has to fit within the curriculum the teachers are teaching,” Studer said. “That’s part of what this USDA grant does — it actually builds a curriculum that meets next-generation science standards so that the curriculum helps teach students those tricky topics.”

The pop-omics curriculum is developed by Studer and his co-primary investigator, who lead a group of teachers that get together and make it fit better in K-12 schools. The teachers then use the curriculum in their classrooms to provide real feedback to do revisions.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“It funds the teacher writing group,” Studer said about the USDA grant. “It funds materials for the classrooms and it funds the research material and it funds the development of materials for each program that I’m getting into.”

The grant enables Studer to collaborate with a 4-H educator and a focus group of students to get detailed opinions and ideas about how to make the curriculum reach a broader audience.

“We test things with them because if we can’t capture their interest, it’s not going to work in an intro biology class,” Studer said. “My goal is to push past 4-H into high school classrooms at large around the state and the country.”

Pop-omics gets students excited about genomics and crop sciences. Students are introduced to the parent popcorn ears and then pop and collect their own data. The data is then used to look at the mathematical trends to decide what variation will be grown the next year.

When talking about the schools he visits, Studer revealed he lets them have and name their own populations.

“One of them is called Cranberry Pop because they’re round and have a cranberry-type color,” Studer said.

With the rapid growth of pop-omics, the research behind it has expanded into computer science, such as building an artificial intelligence model to predict the popping of popcorn from images of a kernel. The AI model will collect and use data from over 10,000 images of kernel-popcorn relationships.

“The program will take parameters out of every picture and then will learn what the kernel looks like and what the corresponding flake looks like that’s popped and then it will start predicting,” Studer said.

Though the focus has been mostly targeted toward high school students, Studer is hoping to reshape the hands-on activities in a way that will allow elementary and middle school students to also experience the pop-omics curriculum.

“The earlier you get them excited about it, the better it is,” Studer said.

Studer also hopes to expand the rapidly growing pop-omics curriculum out of Illinois and reach schools nationwide. The reaction and feedback from students have been described as overwhelmingly positive, with students eager for a visit from the popcorn guy.

“I keep going back because I love the experience so much,” Studer said.