University researchers aim to convert plastic bags to biofuels

March 3, 2014

Each year 31 million tons of plastic goes to the landfill and doesn’t leave. Through his research, Brajendra Kumar Sharma hopes to inspire the addition of another “R” to a familiar phrase: reduce, reuse, recycle — recover.

Sharma, head researcher on this project and senior research scientist at the Illinois Sustainable Technology Center, is specifically looking into the ways plastic grocery bags can be recycled into biofuels. Americans use almost 100 billion plastic grocery bags each year, most of which end up in landfills. But if they don’t, then they are found along roads, in trees and eventually, if not disposed of properly, in water ways and then the ocean, Sharma said.

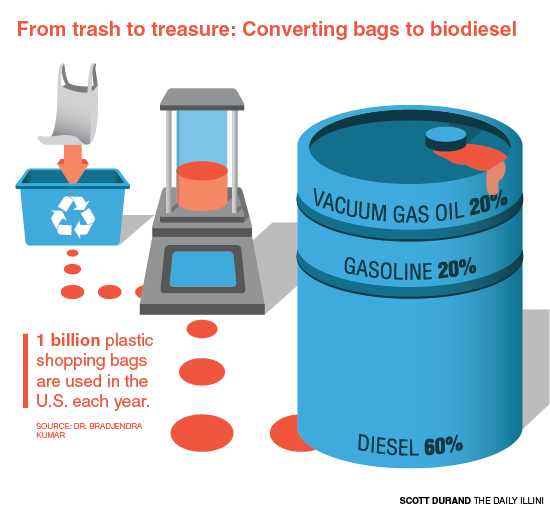

His research aims to break down plastic grocery bags into crude oil before converting it to gasoline, diesel and vacuum gas oil, he said. This process runs at an 80 percent conversion rate, which means eight pounds of material, between 700-800 plastic grocery bags, produce one gallon of crude oil he said.

From the converted crude oil, Sharma said researchers can be converted to 20 percent gasoline, 60 percent diesel and the remaining 20 percent is vacuum gas oil.

Vacuum gas oil can be used as a base stock for producing lubricating base oils that can have various applications, such as two-stroke engine oils, chainsaw oils and other hydraulic oils.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

He said they have not done specific economic calculations but he would guess that the converted oil will be cheaper than the current methods of extracting crude oil because they are converting the material almost for free from landfills and recycling.

“This may be a good source because we have so much plastic that we landfill,” he said. “I am seeing in the future that we may be mining the landfills for the plastics … then taking those plastics and start converting it into oils.”

It is a simple process, he said — the material is heated in the reactor in the absence of oxygen and the plastic breaks down. The oil comes out as a vapor, which is condensed in cold water where the oil floats to the top and can be collected.

Dheeptha Murali, analytic chemist on the project, said she tested the oil after the plastic bags ran through the reactor. Then, she ran it through a system to see where the material boiled because gasoline, diesel and vacuum gas oil boil out at different temperatures. This enabled her to find which materials were present in the crude oil from the plastic bags.

She said it was not tough and is more straightforward than people think it would be, adding that she thinks the more they reach out and explain the research the more likely people will be to support it and recycle their used plastics for making fuels.

“I think this is great and it seems really promising,” Murali said. “This is one way to reduce the plastics in landfills and to make the world greener and cleaner.”

The rates of plastic recovery are low — so far only nine percent of generated plastic is recycled, so the other 91 percent is going somewhere else, Sharma said.

“Even though it is really recyclable, the plastic bags are not being recycled,” said Jennifer Deluhery, process chemist on the project. “People don’t think of it as very valuable material, they think of it as just something very easy to throw away,”

Deluhery said she likes that this process can be used for different types of plastics and she is hopeful to apply this research to harder-to-recycle plastics. Now, the researchers are looking at prescription bottles, contaminated by medicine waste, as a resource for creating crude oil.

Sharma said he hypothesized that within the next two to three years, some commercial plants will be converted to plastic to oil plants. Three companies are already looking into this research in the U.S., he said.

“I don’t think that there is any one solution that is going to completely fix our fossil fuel problem and our energy crisis that we are going to be facing, but I think anytime we can find something that we would normally throw away and get a useful energy product out of it is going to be beneficial to people,” Deluhery said.

Claire can be reached at [email protected].