University research examines gender gap in STEM, humanities fields

January 26, 2015

A recent study found an emphasis of “brilliance” in certain fields led to an underrepresentation of women.

Andrei Cimpian, associate professor of psychology, and Sarah-Jane Leslie, philosophy professor at Princeton, recently conducted research on the gender gap in the fields of science technology engineering and math, humanities and social sciences.

“There are all sorts of stereotypes that have to do with gender, but in particular, we are focusing on the stereotypes about intellectual capacity because these stereotypes, combined with fields whose cultures emphasize that brilliance is needed for success, could lead to female underrepresentation,” Cimpian said.

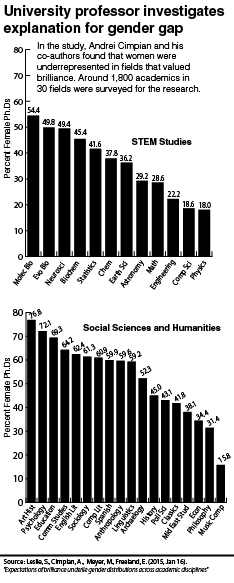

Researchers surveyed around 1,800 academic respondentsin 30 fields about what they thought was required for success in their field. They then studied the relationship between the beliefs of those respondents and the percentage of women who earned their Ph.Ds in those fields.

That relationship showed that fields that emphasized the need to have something special intellectually — “a spark of brilliance” — had fewer women.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“That’s kind of the main finding of the study, which suggests that an atmosphere that emphasizes these innate intellectual traits combined with the stereotypes in our society that portray women as being less likely to possess these traits, is likely to discourage women’s participation,” Cimpian said.

This idea, he said, was then compared to other research, which looks at underrepresentaiton of women in STEM and humanities fields.

“The hypothesis that was most able to explain the pattern of where women were underrepresented across this large stretch of academia was that in certain fields, their culture values brilliance and genius, and therefore women feel unwelcome in those fields,” said Cimpian.

Diane Schnitkey, sophomore in LAS, said it’s never explicit, but she notices there are fewer women in many fields.

“Biology isn’t bad, but I have a research position in a biological physics lab, and everyone in the lab is male,” Schnitkey said. “I’ve never felt actively discriminated against, but I do notice that there is less women.”

The research began when Cimpian and Leslie shared anecdotes about their experiences as a psychologist and a philosopher, respectively.

In their research, they found that philosophy places a lot of emphasis on brilliance, yet according to Cimpian, women hold significantly less Ph.Ds than men.

“‘You need to be brilliant in order to succeed.’ That’s a message that’s conveyed to students and other people who are looking to enter the field,” he said.

In contrast to the field of philosophy, Cimpian said the field of psychology seems to emphasize a professor’s record. For example, what work they have published.

“We’re going to judge you primarily on that basis and convey to our students that those are the expectations that you’re going to be judged by, rather than these kinds of hard-to-judge qualities about who’s brilliant and who’s not,” Cimpian said.

Angela Wolters, associate director of Women in Engineering, said she feels a shift happening.

“There has been such a national and or international focus on women in STEM, that when it comes to the engineering field, when it comes to the concentration in other STEM oriented fields, that we will continue to see that shift,” she said.

She mentioned studies that have shown that men and women come out of high school equally prepared to study engineering. In the past, she said, women weren’t taking calculus or physics and thus were less prepared to move into the engineering field when they entered college.

With more opportunities that now exist, she said, more women are deciding to study in different fields, regardless of stereotypes.

Stephanie Lona, senior in engineering and president of Women in Engineering, said the gender gap may continue to exist, but she thinks progress is being made.

“It will never be closed within my lifetime,” Lona said. “I think that it will always exist. There will be that stereotype that men are supposed to be engineers and that women are supposed to do housework, even though that’s completely changing, and the gap is closing, but it’s still an upward battle.”

Jane can be reached at janelee5@dailyillini.com.