Don’t use hobbies for career advancement

October 9, 2018

The question, “how’s your semester going?” can pop up at any given time, but asking mid-semester often garners a lack of enthusiasm – at least from me. Knee-deep in assignments, the only response I can give is regarding how busy I am and my lack of free time. It’s true, I am busy, but so is the guy who has been seated next to me at Grainger Engineering Library for five hours now.

I’m starting to think it’s not just time restrictions prompting me to cast m—y hobbies away as a thing of the past. While a study done by the Journal of “Occupational and Organizational Psychology” shows that pursuing a hobby boosts productivity levels at work, it’s important you separate these hobbies.

When you’re mired in a self-imposed perpetual pursuit of the conventional definition of success, the idea of leisure may come off as absurd. It presupposes that we have overcome the Catch-22 of balancing a social life, adequate sleep and achieving good grades.

Worse still, the importance of doing things solely because we enjoy them is overshadowed by our achievement-oriented culture. Hobbies have morphed into tools to develop one’s career, turning the things we purportedly do for fun into more work.

Sometimes, it feels as if my current work ethic is geared toward my future autobiography; my story will begin with endless hours invested into my craft, leading me to success. If I throw myself into university life with aggression and persistence, I will achieve all my goals, right?

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Initially, the adrenaline rush of crossing things off my to-do list was sufficient in fueling this mindset. But the satisfaction or feeling of accomplishment from achieving something is lost. The feeling will linger for a minute before the ultimate purpose returns as motivation to strive even harder to achieve the next goal, feeding into the vicious cycle of workaholism.

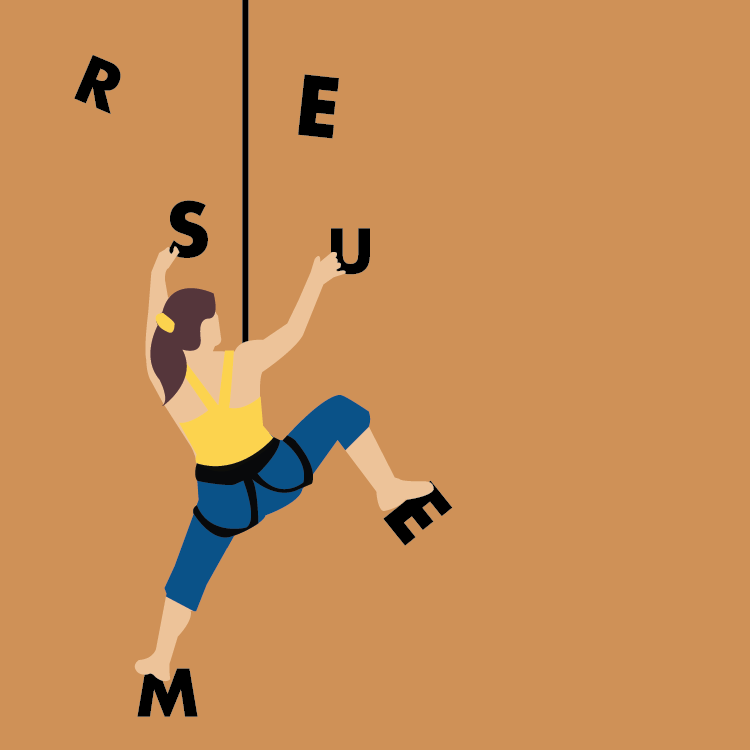

Why sign up to spend four hours of your week at beginners’ dance practice if it will not contribute to the “Leadership Experience” space on your resume? Can you call yourself a rock climber if you struggle to send a 6b route? There is nothing wrong with setting goals and working hard to achieve them, but when our expectations have stultifying effects, it’s telling of the loss of the true meaning of the word “hobby.”

In retrospect, the moments that stick with us are those spent on the learning curve, doing and undoing in order to arrive at the final result. The pure childlike delight in learning a new skill, to take pleasure in the mere act of doing, is what we need to return to. Permitting yourself to do only things you excel at depicts the pairing of exceptionally high expectations of yourself with exceptionally low confidence in your abilities, both of which highlight the issue of self-judgment.

Fast forward into the future: you’re in your 40s, and pre-mid-life crisis presents you with a sudden desire to take up paragliding classes. Enter post-mid-life crisis at age 60, which prompts you to finally run that marathon – an unattainable goal you once had as a busy college student. However, whether the activity be physical or sedentary, achieving excellence in your endeavors usually comes with the preconceived notion that you must start young. The expectation of excellence should not be a limiting factor to these pursuits, especially during your college years, a time where you have the freedom to explore, and physical health to complement it.

The funny thing is, I write this as I enter hour seven of my 12-hour Saturday at Grainger, hence forgoing the weekly climbing sessions I used to make time for. Maybe it’s time I heed my own advice.

Kimberly is a junior in Engineering.