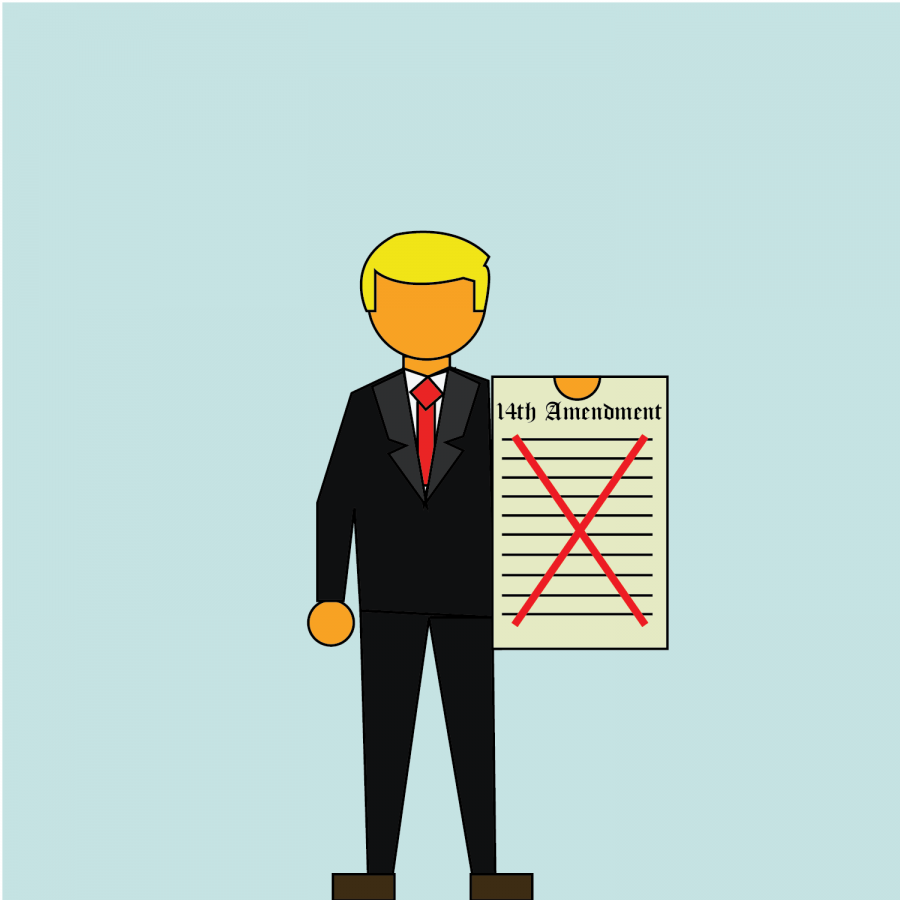

Eliminating birthright citizenship ignores history

Nov 8, 2018

President Trump has toppled many presumed norms and policies in his two years in office. His latest assault is on birthright citizenship, something previously viewed as such a vital cornerstone of our American values that even the Supreme Court hasn’t questioned it in over a century. President Trump is suggesting he could end the citizenship of people born on U.S. soil — specifically, those born to noncitizen and undocumented parents — with an executive order. That change would drag U.S. immigration policy and suffrage rights back to the late 1800s.

The debate on citizenship is really a debate about power — who gets to vote? It should come as no surprise that President Trump has made this an issue just days ahead of an election that could make or break his legacy. Ever the “very stable genius,” Trump understands that the fear of sharing power with outside groups will motivate his base and further divide the country.

Birthright citizenship has largely been considered settled law since 1898 when the Supreme Court decided the seminal case U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark. The ruling reaffirmed the first sentence of the 14th Amendment, which reads “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.”

At its core, the administration’s argument focuses on one phrase: “under the jurisdiction thereof.” It argues children born to undocumented immigrants are not subject to the political authority of the U.S. and, as such, do not qualify as citizens.

Hans von Spakovsky, a conservative legal scholar and manager of the Heritage Foundation’s Election Law Reform Initiative, describes political jurisdiction as the ability of the government to compel someone to serve on a jury, to be drafted to the military should the draft be reinforced and, principally, to owe allegiance to the U.S.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

To argue the children of undocumented immigrants are not subject to the political jurisdiction of the U. S. is illogical. Spakovsky, like the Trump administration, is conflating undocumented immigrants with their citizen children. As citizens, they have all the rights and responsibilities all Americans have. They have Social Security numbers and receive government benefits, but they also serve on juries, pay taxes and enlist in the military in large numbers. They fall fully under the political jurisdiction of the U.S., and to argue otherwise is to openly discriminate against hundreds of thousands (or possibly millions) of citizens who actively contribute to the welfare of this country.

The U.S. history of citizenship and immigration is inextricably intertwined with the right to vote. The reason the 14th Amendment was enacted was to ensure newly freed slaves in the South were granted citizenship.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was a precursor to the 14th Amendment and was introduced and signed into law two years before the amendment. In a debate on the floor of the Senate, one senator asked another if under the language of the act, “It will not have the effect of naturalizing the children of Chinese and Gypsies, born in this country?” The question itself underscores our country’s haunting long-held fear of expanding the privilege to vote beyond white Anglo-Americans.

The Trump administration’s attempt to redefine citizenship appears eerily similar to debates held in the aftermath of the Civil War about the repercussions of granting citizenship to minorities.

It’s uncertain how this policy proposal would play out in the courts, but on its face in these early stages, it looks like it is dragging American immigration law all the way back to the 19th century.

Kyra is a sophomore in LAS.