Opinion | Ranked-choice voting: It’s as easy as one, two, three

Mar 27, 2019

Government reform is egregiously needed in America but seldom discussed, specifically regarding elections. This extends to redistricting reform — which has gained momentum in recent years — campaign finance reform, the question of making Election Day a federal holiday and, as some even discuss, replacement of the electoral college.

However, one severely underrated proposal is the implementation of ranked-choice voting. Ranked-choice voting can help correct established and fundamental issues with our democratic system.

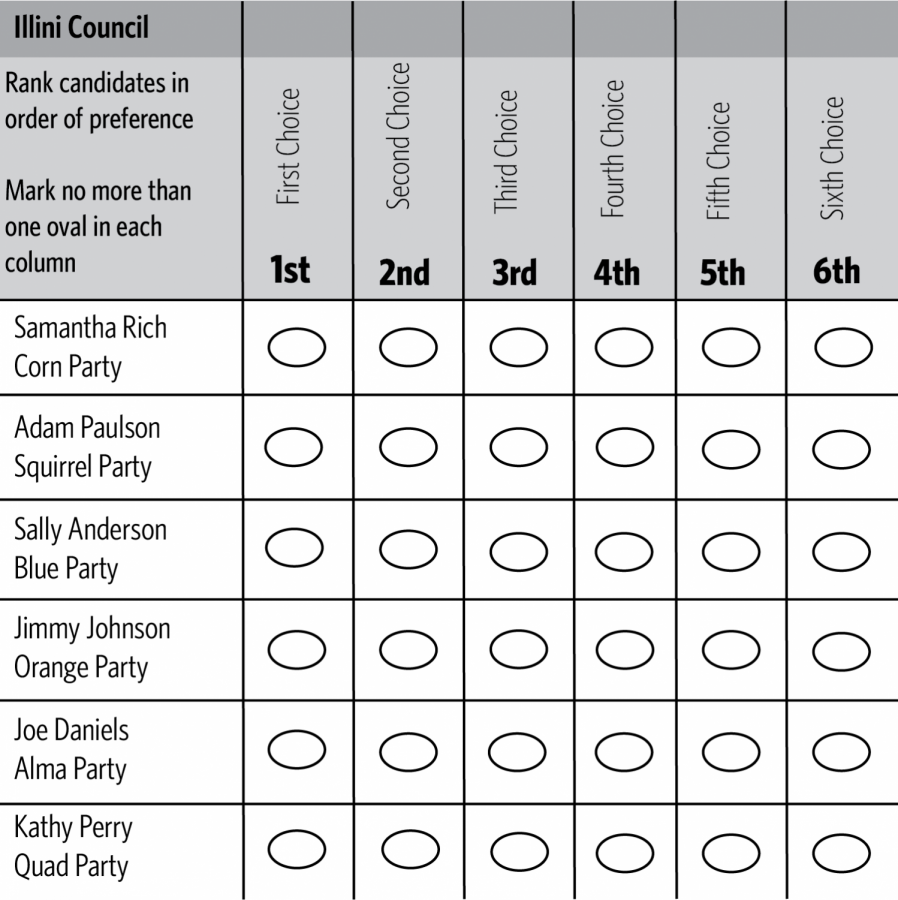

The easiest way to explain RCV is that it is a way of voting so a single election may be held with automatic runoffs if no candidate receives 50 percent plus one votes. The ballot would be amended so a voter could choose a first-choice candidate, second-choice candidate and third-choice candidate.

In a less technical sense, once all the votes have been counted, if there is no candidate with a clear majority, the candidate with the lowest number of votes is eliminated and all voters who put said candidate as their first choice will now have their second choice considered. The process of eliminating candidates and considering those voters’ next choice continues on until there is a candidate with a majority’s support.

The implementation of ranked-choice voting brings with it a list of significant benefits. One obvious benefit is now candidates would be elected by a majority, not a plurality. Politicians couldn’t win with 40 percent of the vote as some have in the past; they would have to win at least 50 percent. This guarantees the ones being elected into office are popular with the public and could help improve currently low approval ratings of politicians and government overall.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Another benefit is ranked-choice voting could break the two party system in the U.S. and be more inclusive to other parties. Many do not vote third party, fearing their vote will be wasted. With RCV, listing a less popular or lesser known candidate as one’s first choice does not equate to a wasted vote, as long as the voter has recorded a second and third choice.

Two less intuitive benefits: RCV engenders friendlier campaigning (and in turn less mudslinging in campaigning) and may mitigate the impact of money on the political process.

RCV causes less mudslinging because candidates, in a larger pool, knowing they can be a voter’s second or third choice, tend to rely less on the strategy of criticizing the other main candidates and rather focus on themselves as a candidate and their issues.

Furthermore, candidates would be fearful of criticizing opponents, knowing they are able to be the second or third choices of those opponents’ ardent supporters. No longer would voters feel they have to vote “against the other candidate,” but rather could vote for the candidate that resonated most with them.

Preliminary studies show the candidate with the most money may win less in a system with RCV than in a conventional plurality system. The impact of money on politics may be controlled because voters can feel like their vote will not have been wasted by voting for the grassroots candidate rather than the well-funded one.

RCV could have significantly changed the outcome of elections had it been implemented sooner. As just one example, in the election of 1912, Woodrow Wilson won primarily because the Republican Party was split between two candidates: Theodore Roosevelt, who had become a progressive at this point, and William Taft. Wilson won with 42 percent of the vote because of the split Republican Party. This phenomenon — known as the “spoiler effect,” where two ideologically similar candidates rob votes from one another — is rectified by RCV. Similarly, RCV had the potential to sway close elections such as the 2000 or the 2016 presidential elections.

Opponents’ criticisms have generally arisen from a misunderstanding of how RCV works. One major criticism is it alienates the unspoken democratic principle of “one person, one vote.” But many countries have a democratic majority system with runoffs, namely France and Nigeria, and they would likely debase this criticism in the same way: In the end, every person’s vote has the same weight.

Other opponents say RCV is too complicated. However, once explained, the system is very easy to comprehend. Even if the voter still prefers the conventional method of voting, they can still list one candidate and leave the other two options blank, bearing the exact same weight as before. Few criticisms against this system actually hold water.

The system of voting has already been implemented in countless municipalities and in one state — Maine. Its 2018 midterm elections served as evidence to back up claims about RCV’s benefits. Maine’s 2nd Congressional House District was one of the last races called. The Republican candidate had a plurality, but not a majority. Two candidates unaffiliated with the two major parties had received a fair number of votes and as they were eliminated, the Democratic candidate was declared the winner. Ranked-choice voting single-handedly changed the outcome of a House race this year.

In Illinois, the issue was discussed during the gubernatorial race. State senator and Democratic hopeful Daniel Biss placed the issue on his platform and introduced the bill in the Senate. Also, libertarian Kash Jackson says he would sign a ranked-choice voting bill if it reached his desk. Gov. J.B. Pritzker has not indicated clearly whether or not he supports the measure, but says he would like to “study its effectiveness.”

Ranked-choice voting is a small reform that could remedy many of the electoral ills plaguing the U.S. today. The first step towards nationwide implementation is to spread awareness of this better system of voting. Perhaps in 10 years, all of America will be voting this way and everyone will wonder why voting hadn’t always been as convenient as one, two, three.

Andrew is a freshman in LAS.