Researchers invent ‘microbubblers’ to destroy harmful bacteria

November 15, 2018

Biofilms, or surface-sticking clusters of bacteria, cover everything from bathroom floors to medical devices and are a major cause of hospital infections. These collections of dangerous cells are tough to crack and require thorough scrubbing to be removed, but what if they live in spaces too small to reach?

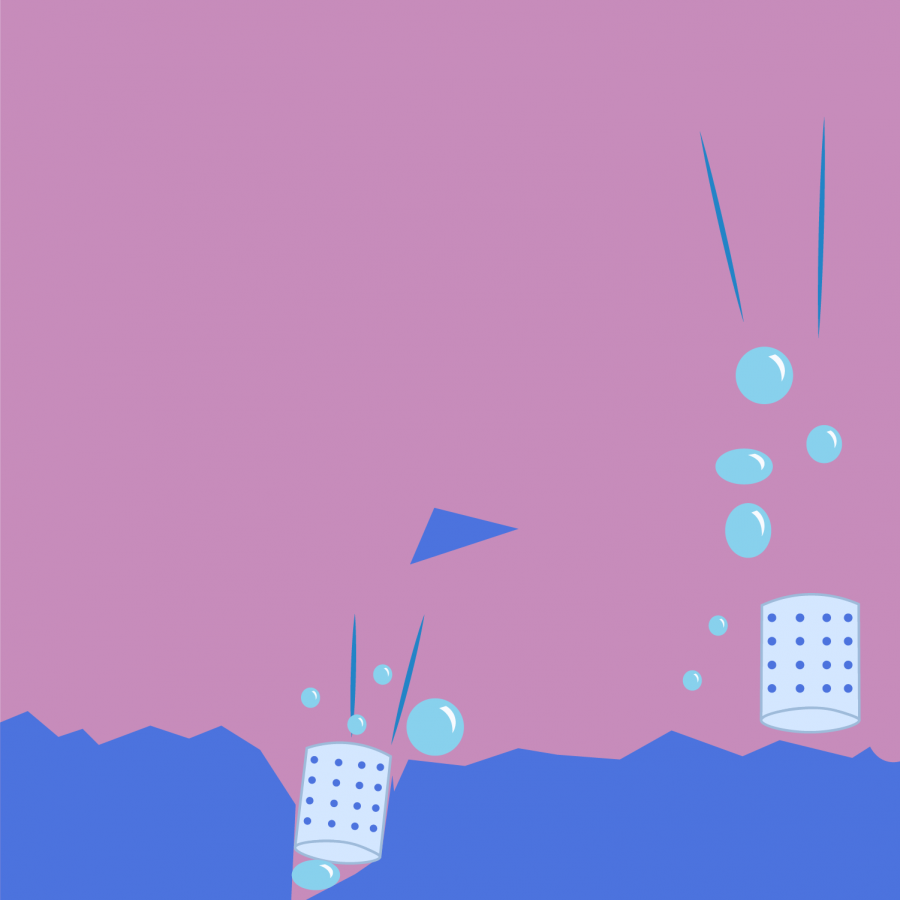

A team led by University researchers has invented a possible solution they call “diatom microbubblers,” or tiny, cylinder-shaped particles that generate oxygen bubbles to move around and break up biofilm. As detailed in a paper published in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, these objects lodge themselves in biofilm before creating lots of bubbles, which expand and dislodge the bacteria.

“If you simply pour Clorox (on a biofilm), it’s not going to work right,” said Hyunjoon Kong, professor of bioengineering. “Biofilm limits the transportation of these molecules, so the Clorox may not have gone into the matrix easily.”

But once the bacteria are dislodged by the diatoms, a hydrogen peroxide-based antiseptic like Clorox can kill them much more quickly. This is especially useful in eliminating bacteria colonies that may be hiding in tiny scratches or holes throughout bathrooms or hospitals.

“To sterilize needles and other medical devices, you need to remove the bacteria and other organisms in that medical device,” said Jun Dong Park, University postdoctoral student. “Medical devices are very small, so you cannot physically remove the bacteria; we may use this kind of diatom microbubbler to remove those bacteria.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

To create the microbubblers, the team took porous, silicate-based skeletons of dead diatoms — a type of single-celled alga — and treated them with a manganese dioxide coating, which generates oxygen bubbles when in a hydrogen peroxide solution. The bubbles would accumulate before being expelled out one end, propelling the diatom through the solution like a microscopic jet ski.

The researchers then aimed the treated diatoms at biofilms in small crevices.

“They can penetrate the thick biofilm and make a bubble inside to break down the biofilm,” said Yongbeom Seo, University postdoctoral student. The diatoms would continuously produce bubbles, which grew in size and pushed against the bacteria until the biofilm shattered and the hydrogen peroxide sanitized the entire sample.

Over several tests, the researchers demonstrated a hydrogen peroxide solution mixed with diatoms was significantly more effective at sanitizing a biofilm sample than the antiseptic alone. Several members of the research team see great humanitarian potential in this result.

“Biofilm can cause foodborne disease, where $8 billion are used every year,” Seo said. Kong said biofilms pose threats in other contexts like heat exchangers, airplane fuel tanks and shower heads.

Seo said the involved materials are generally harmless for both the environment and humans — the silicate cell is unreactive and the manganese is biocompatible — but the team plans to further test the efficacy and safety of its diatoms.

The researchers see potential in their invention beyond effective sanitizing. Seo said he wants to further study microscale collisions involving the diatom, while Park is interested in using the diatom as a tool to investigate other materials and mixtures.

“If we put the diatoms in a solution, it can be considered an active particle, and by analyzing the active motion of the diatom, we can get the information about viscosity and elasticity,” Park said.

An extensive team of researchers executed the development of diatom microbubblers. Involved members came from the University, the National Institute of Aerospace, NASA, the Korean Institute of Industrial Technology and the Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology in Singapore. The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and the Korea Institute of Industrial Technology.