“Dating is hard” — that’s how a lot of great columns start. But this isn’t “Sex and the CU,” this is me, which means we’re going to have to talk about economics.

I’ll relent and say that, vibes-wise, dating sucks. Structurally, it’s an imperfect market. There isn’t necessarily a match for everyone, and your odds scale almost entirely with the number of people in your immediate orbit — tough luck if you’ve already exhausted the dating app pool. The apps themselves are an imperfect solution to a problem created by suburban sprawl, car dependency and the disappearance of third places where people used to meet each other by chance.

Those are just the barriers to getting dates. Now — excuse me while I get up on the soapbox — let’s say you clear them. You’re no longer swiping, you’re no longer strategizing, you’re officially “dating.” This is the part that’s supposed to be fun.

And yet, where is the joy?

Somewhere along the way, we’ve gotten away from dating as a low-stakes endeavor. It’s expensive, and it seems like even the most lowkey of plans demand a budget, a reservation and a triple-check of your bank account — as if intimacy itself requires authorization.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

There’s an economic model that can help formalize this under the umbrella of “leisure” — defined simply as any hour not spent working, treated as interchangeable with any other. It’s a useful abstraction, yet wildly insufficient.

That assumption breaks down almost immediately in real life. Dating doesn’t just require free time; it requires unstructured time. I’m not usually this precious about semantics, but the distinction matters. Leisure, in economic terms, is not the same thing as unstructured time. An exhausted hour wedged between obligations may count as leisure on paper, but it’s functionally useless for intimacy.

More importantly, many people don’t get that kind of time at all. Hourly workers, gig workers and caretakers live with schedules that shift week to week — or day to day — leaving little room for spontaneity. The same goes for salaried young professionals: They over-optimize their calendars, prebook their evenings and treat weekends as recovery periods instead of opportunities for connection. When everyone’s busy, no one gets to capitalize on the joy of connection.

From an economic perspective, this isn’t accidental. Americans work more hours, on average, than workers in most other rich countries. At the same time, “nonstandard work” — like gig labor, irregular schedules or multiple jobs — has expanded, reinforced by a cultural moment that treats constant productivity as a virtue. Side hustles monetize hobbies, downtime becomes suspect and free time starts to feel indulgent.

Dating, then, runs headfirst into “time poverty,” a simple lack of unstructured time. Not because people don’t want connection, but because connection is one of the few things that still demands inefficiency. You just can’t optimize it, squeezing it neatly between obligations.

Romance doesn’t survive in the margins of your Outlook calendar — and yet, structurally, that’s exactly where we’ve tried to put it.

Time isn’t the only constraint. The baseline cost of a “normal” date has gone up as the cost of everyday life has risen faster than young people’s incomes. The Institute for Youth in Policy has documented how, even as inflation has cooled, essential costs like housing, transportation and food have remained structurally higher, while real wage growth for young workers has been uneven and volatile.

Persistent rent pressure and housing shortages have pushed many young adults into extended roommate living, limiting access to private space and quietly shifting intimacy into public settings — whether it’s cafes, bars, restaurants or rideshares — that charge for time, whether spending is the point or not. Dating becomes more expensive not because of higher expectations, but because the material conditions of young adulthood leave few genuinely low-cost alternatives.

None of this is happening in a vacuum. It maps neatly onto a broader pattern of spatial hollowing-out. As expected, the third places that once made casual connection possible — the spaces between home and work where you could exist without a transaction — have steadily disappeared. What remains increasingly operates on a pay-to-exist model.

That explains why a request for dating advice now turns into a scavenger hunt for the last remaining places where you can simply “be.” In Champaign-Urbana, that list is getting shorter, but it still exists: connecting over coffee at Caffe Paradiso, walking the paths around Japan House, browsing the shelves at Jane Addams Book Shop or simply existing together on the Main Quad when the weather allows it.

I came up with these off the top of my head, and I’m confident you’re more creative than I, dear reader. The world is your oyster. The problem is that oysters are getting harder to find when nearly every space asks for a credit card. If every place requires a purchase, intimacy becomes a luxury good.

It’s worth noting that the norms around dating — what counts as effort, what counts as acceptable and what reads as thoughtful versus cheap — are increasingly set by people with disposable income and time. Deviating from those norms carries real embarrassment risk.

But don’t let that deter you — in equilibrium, nothing fundamental has changed. People still want connection and intimacy. What has changed are the institutions around dating: labor markets that consume time, housing markets that erode privacy, cities that price out unstructured space and cultural norms that treat inefficiency as failure.

The problem is misdiagnosis. When dating is framed as a personal failure rather than a structural one, the conditions making connection more difficult become opaque. The sooner we understand this as an institutional failure rather than an individual one, the sooner we can stop wallowing in material conditions and start rebuilding the spaces and norms that make connection possible.

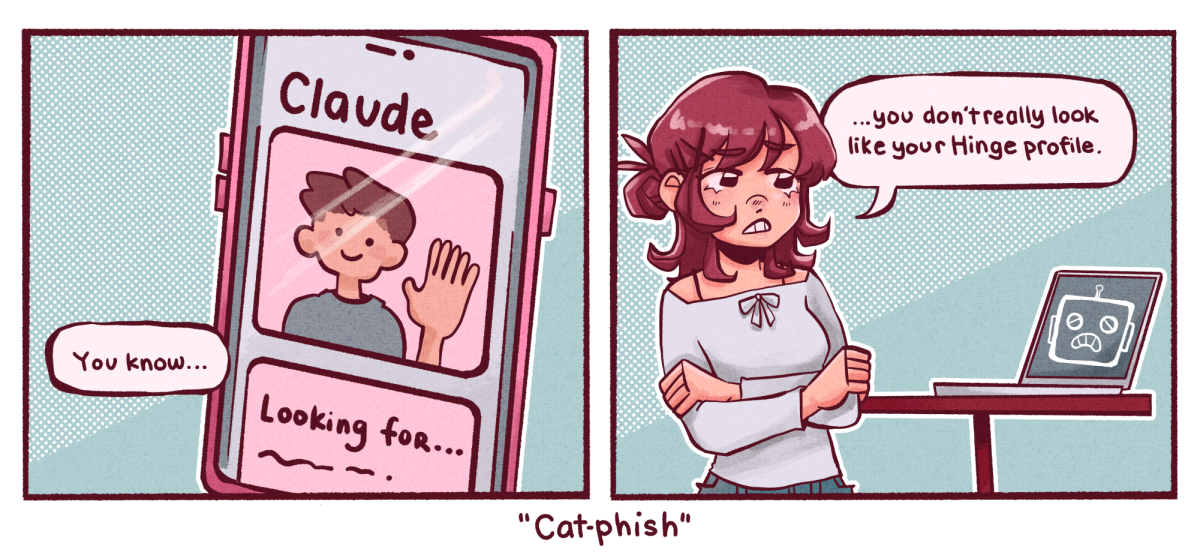

Raphael is a senior in ACES and unfortunately did download Hinge — don’t bring it up with him.