Located within the Carle Illinois College of Medicine are several 3D printers produced by the mind of Rand Kittani, graduate student studying Medicine. She established “the world’s first business school 3D printing lab,” and her ideas continued to flow from there.

Kittani encountered REALETEE, a company based in France that used similar 3D printers to create high-end breast prosthetics. She knew the same thing could be done at the University, but her focus was different: She wanted the prostheses to prioritize those wearing them.

“I have a lot of empathy for patients going through cancer,” Kittani said. “It’s devastating. It’s not easy for any member of the family to get it, but let alone, if you’re a mother … it’s even more amplified for their families, and women go through a lot just by nature.”

As the student lead on this project, Kittani works closely with Dr. Victor Stams — the project’s clinical lead, professor in Medicine and Carle Foundation Hospital plastic surgeon — and a team of four students. Kittani and her team conduct studies in his clinic to gather patient input.

After an interview with a patient, the team learned about the waiting period between getting a mastectomy and an implant. Most plastic surgeons recommend that patients wait until around six months after they’ve undergone radiation treatment to consider breast reconstruction surgery, providing ample time for the skin to heal.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

To alleviate the psychological effects, like depression, anxiety and stress, that this period can have on patients, the team is working to bridge this gap in time.

“Vision matters,” Kittani said. “Everybody’s on the same page in terms of where this is going, and we all kind of realize how this will be important for patients … It’s been amazing to see how different expertise can come together to build this.”

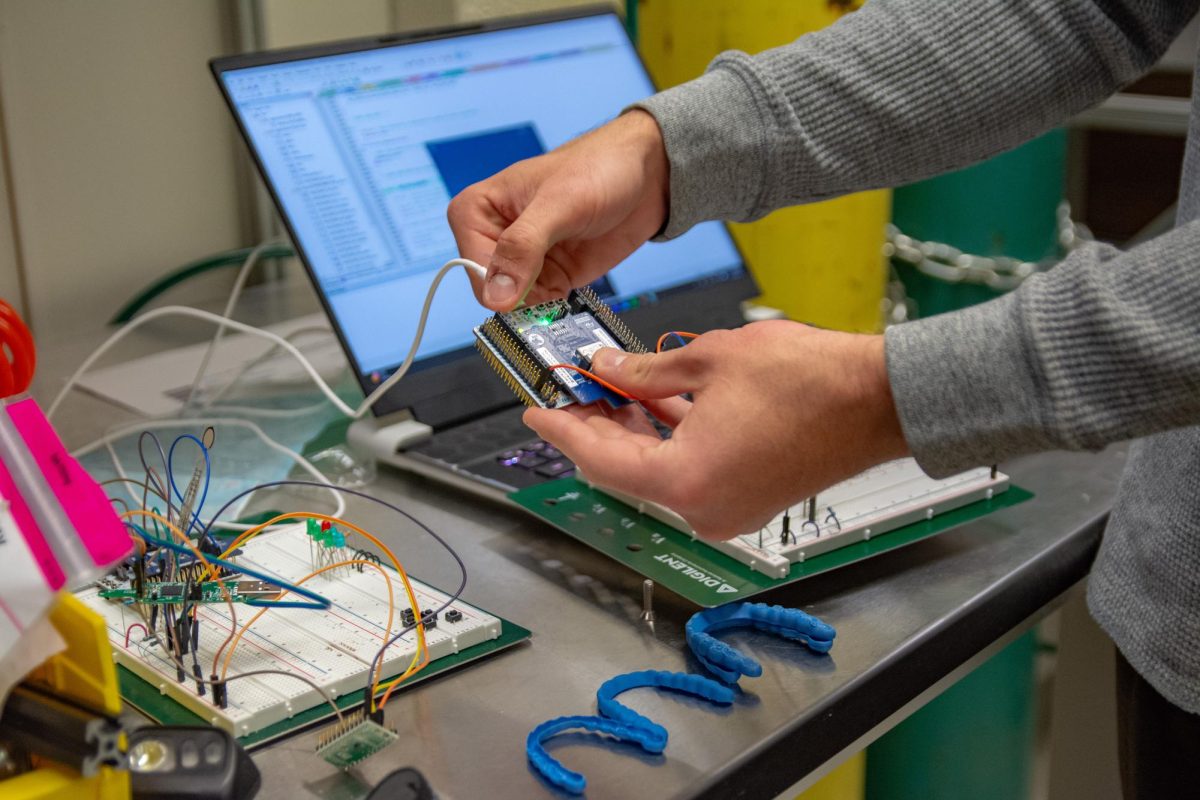

The team first uses a 3D scanner to examine the breast before the operation. Once the scanner forms the image, they place it into their developing software, where doctors can minimally manipulate the depiction and print a 3D custom-fit breast prosthesis.

“One of the challenges we have is: How do we make a unique software with all the technologies out there?” Kittani said. “How do you come up with something that is not out there, but it’s easy to use, but it’s keeping up with the technology and having it done in six months or less than a year?”

Despite Kittani’s questions, Stams noted how Kittani came up with an idea “that was right in front of our eyes.” He has watched her constantly ask what more they could do with the device.

“She had the ingenuity to sort of say … ‘Can we not take this device, create a mirror image of a patient’s breast and then deliver them a prosthesis that actually fits, restoring their dignity (and) integrity in a sense of pride?’” Stams said. “And she’s been able to achieve that. Pretty remarkable.”

Stams further mentioned that even though the product remains in a development phase — as they look at what materials work best, how to produce on a mass scale and several other unanswered questions — the reactions have been overwhelming. Patients whom he’s never met before have reached out to him about the device.

The team has questioned how they’d market the prostheses, and Kittani and Stams said they’ve decidedly focused on underserved areas and patients without access to care. Simultaneously, they’ll collaborate with doctors so that patients receive adequate information about the options ahead of them.

“If we understand that, for many patients, prostheses are not a cosmetic luxury, they’re part of restoring a patient’s well-being,” Stams said. “We’re trying to bridge that gap by creating a device that’s cost-affordable and effective for patients, not only (those who) are underserved but for all patients.”

High-quality breast prostheses can cost anywhere between $100 and $500. Custom-made prostheses can increase that price by thousands.

The Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act of 1998 requires that health insurance issuers that cover benefits for mastectomies must also provide coverage for certain benefits post-mastectomy. However, the law excludes Medicare, and individuals hold responsibility for co-payments and deductibles as a result of their breast prostheses.

Kittani created a product meant to be easily accessible for patients: something quick and low-cost to aid them through their battle against cancer, even if it’s only a fractional support along their journey.

“My goal (with) this technology is not just to come up with something and put it out there,” Kittani said. “I actually want it to be patient-centered and desired by patients.”

To Stams, the project also holds significant meaning for the Champaign-Urbana community. He said that his patients get to witness a remarkable idea coming to fruition, and they don’t have to travel far to do so.

“Oftentimes, we’re looked at as a very small medical college … but the students that we have at this college are just world-class,” Stams said. “We have the best and brightest students in the nation, students from all over — from the East Coast, from the West Coast, like Rand — and they all come here to this think tank.”

Since the team has a proof of concept, the next step is to establish more elaborate processing. They’ll work toward using a computer-aided design software to facilitate going from scans to prints, alongside ensuring the product follows government regulations.