Nation’s best has long history on pommel horse

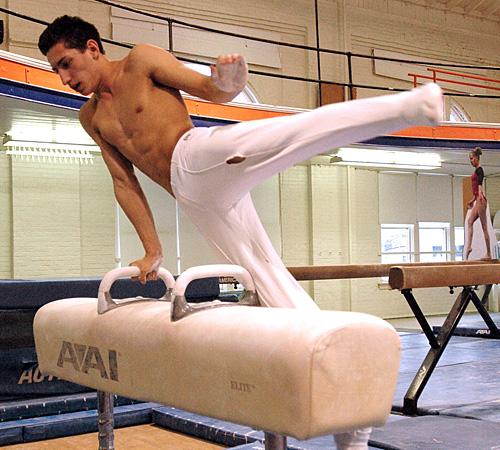

Freshman gymnast Daniel Ribeiro practices on the pommel horse at Kenney Gym on Feb. 12. Erica Magda

February 19, 2008

Daniel Ribeiro looks at ease in the gym. He deftly moves from event to event, trying to get as much as he can out of each. He finally makes his way toward his best event, the pommel horse. While he maneuvers on the apparatus, his feet and legs remain without a break as if fused together. As he uses each handle, Ribeiro almost looks a little bored as he shows his skill and why he is ranked No. 1 in the country on the apparatus.

The son of John Ribeiro, a former Brazilian Olympic gymnast, and Michelle, a lifelong gymnast as well, Ribeiro has spent more time in a gym in 18 years than most will in a lifetime. His parents took a unique approach to raising him and it shows. His path to gymnastics was one that might not have come about, but it appears he was meant to be drawn to the sport his parents have left their mark on.

But given the fact that Ribeiro, a freshman from Chestnut Ridge, N.Y., has been in the gym since he was 13 days old, it’s not hard to understand why he seems to be at ease. And until recently, things had been easy for Ribeiro. However as of late, he has dealt with the pressure that comes with being the best in the nation on the pommel horse.

The family business

Rather than try to live vicariously through his son, John said that he “didn’t want (Ribeiro) to do gymnastics” because of the time commitment. His mother, on the other hand, wasn’t opposed to him taking up the sport; she told Ribeiro that if he did, that he would devote himself entirely to it.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“I always said to both my kids it was going to be mandatory for them to be busy doing something,” Michelle said. “It can be whatever they wanted. It wasn’t a matter that I ever pushed him to do the sport, but the thing about gymnastics is that it is a really unforgiving sport. If in gymnastics you are kind of out of shape, you can’t do it. If you’re practicing to do a double back (flip) and you don’t work out that much, you’ll be killed. (Constant practice) is what it takes to do competitive gymnastics.”

Aside from their history in the sport, Michelle and John own and run U.S. Gymnastics Development Center II, a developmental gymnastics facility in New York. The facility boasts four scholarship athletes and multiple junior champions, both male and female, and most notably, their son.

But when it came to Ribeiro, it was John who was more apprehensive about pushing his son into the sport.

“It was really fun, but it was so hard at the same time because of who my parents are,” Ribeiro said.

John knew the problems that came with gymnastics.

“I tried not to push him into the sport,” John said. “You’re always training, always in the gym, so I tried to get him to do other sports. He was never one of the best as a junior; it wasn’t until later on and now in college that he has excelled.

‘Throwing’ it all away

Ribeiro competed in the sport unabridged for the first 12 or so years of his life. He then experienced “the lull” that the three Ribeiros all said is something that is inevitable for most every gymnast. This refers to the point in a gymnast’s career when the work load becomes too much and too time consuming to conceivably continue in the sport.

As per Michelle’s rules of parenting, Ribeiro was allowed to back off of gymnastics, so long as he kept active in something else. That something quickly became baseball when Ribeiro discovered his passion for the sport.

“I would spend hours at the gym and sometimes I would get bored of the crazy things that I could do in the gym,” Ribeiro said about the beginning of his foray into baseball. “So I would sit in front of the TV and a lot of times the Yankee games would play and I fell in love with them.”

His love affair coincided with maturity and a pubescent enlightenment.

“At that point in seventh grade was the first time that I realized that I had a mind of my own,” Ribeiro said.

Looking back on the understanding years later, he says it jokingly, but still with a hint of realization in his voice that suggests he honestly may have not considered other options until then.

“What if I didn’t do gymnastics? Is that a possibility? Let me see if I can try baseball.”

With the blessing of his mother and ever-present support from his father, Ribeiro ventured into something new.

“From then on, I wanted to play,” Ribeiro said, “and I started to around seventh grade. I loved it, and I was terrible, I was so bad. It got to the point where I would calculate my batting average, it was like a .042. I got one hit in like 25 at bats or something. But I think it helped that I had that for a time, it kept me sane.”

That sanity gained from his newfound outlet is something Ribeiro said likely furthered his devotion to gymnastics. His career in baseball may have never caught the eye of Derek Jeter or George Steinbrenner but nevertheless provided a release from his lifetime of work in the gym.

John, too, had his own conflict of sporting interest growing up. Like many children growing up in Brazil, he had an affinity for soccer at an early age.

“I always played soccer, and I was pretty good at it,” John said. “I was on the traveling team, but my gymnastics coach said, ‘Enough, John, either soccer or gymnastics.’ When (Ribeiro) wanted to play baseball, I pushed him into that; I didn’t want to push gymnastics. It’s so sad when you get older if you see you had a bad childhood because of being pushed.”

Like father, (not) like son

The link between the father’s and son’s departure from gymnastics may be one of the few things that the two shared in athletics.

Ribeiro’s abilities in gymnastics weren’t that great by his own admission early on; it was more so the constant time in the gym that kept him in the sport. As time went by, however, he started to develop with an event that was one of the least likely – the pommel horse – which John said was one of his weakest, if not his worst.

As Ribeiro’s skill in the event continued to blossom, it became apparent that he would likely not take the same path toward gymnastics that his father did.

“The thing for us was, Daniel is really, really gifted on pommel horse; he really seems to be world class on the event,” Michelle said. “I was never that great of a gymnast but my husband was. He will just say to me every night when we watch (Ribeiro) train or tapes of him; he just can’t even believe he’s our son.”

Ribeiro knew once he started to become more and more dominant in the event that it was an unlikely development, but it was something he still found was meant to be.

“That’s his worst event; I look it at as he gave me something from his genes that he didn’t have,” Ribeiro said about his father on the pommel horse. “It is weird because he went to the Olympics, and he tells me straight out that I am twice as good as him, as he ever was. That says a lot to me, confidence-wise, it really helps me stay focused and stay confident with everything that I do.”

Feeling the pressure

That confidence and focus finally came to a head during his senior year of high school. Ribeiro always did extremely well on the horse but he faced his last opportunity to reach the pinnacle of his sport before going to college.

By this point, he had gone through enough repetition and turns on most every event that one would think he would be comfortable with the pommel horse, taking second the past two years at Nationals. But as well as Ribeiro did, with his skill came a habit of placing “ridiculous amounts of pressure” on himself.

“It was so stupid of me, but I looked at the score of the guy before me and he had a like a 9.4 (out of 10),” Ribeiro said about his senior year at Nationals on the pommel horse. “So I had to pretty much have a perfect routine with no major deductions or I was going to come up short again.”

The countless hours of practice, the pressure of college pending, the weight of living up to his own expectations that had increased exponentially since just two years earlier; all of his time in the sport culminated in his performance, one that won the Junior Olympic National Title and helped him earn his now No. 1 ranking on the event in college.

“A lot of people said to me after, ‘When you’re in the zone, you’re calm and confident’; I was nervous, I was shaking out of my mind,” Ribeiro said about facing the last time on the event as a junior. “Deep down, I was scared. I remember going through my head before I went, I think I’m having heart attack.”

Still remembering the event, he shifts in his seat and starts to speak louder and faster.

“I was shaking to the point where I almost couldn’t move. But the second the judge saluted,” he takes a breath and pauses, the same that he did then. “I remember thinking about everything I’d done, took a breath and flowed through it.”

His career in gymnastics has seemed like a cakewalk since that day.

A scholarship to the University, coming into the season as a favorite to win the pommel horse in the Big Ten and, most recently, gaining the No. 1 ranking in the country.

It seems all too easy for Ribeiro from the outside looking in – the pressure, his storied history in the sport, everything else that has come with it. Maybe it is.

That’s fine by him.