Valentine’s Day: A not-so-sweet origin

February 13, 2014

The date is Feb. 14, 1817. A young man eagerly pens a Valentine’s Day poem for the young lady who has caught his fancy. Taking great care with the rhyme and the card, he hands it off to the postman and awaits her reply.

Shortly thereafter, he receives a lace-covered Valentine’s response, but alas, no good news. She writes: “If truth must be told/You cut it all too fine,/You’re a smart-looking blade/But no favorite of mine.”

Valentine’s Day has always had roots in bringing people together, with positive or negative results. As illustrated by the poem in Ernest Dudley Chase’s 1926 book, “The Romance of Greeting Cards,” verbose poetry was once a key component to the holiday, along with greeting cards and illustrations dating back before the 1800s.

But how long have people been professing their love to each other on Feb. 14? According to legend, the amorous holiday has roots in Ancient Rome — but it’s not all chocolates and roses.

St. Valentine was a Roman priest living in the third century, according to one popular tale on History.com. During this time, Emperor Claudius II banned Roman soldiers from getting married, claiming that they fight better without a woman in their life. St. Valentine, wishing for love to prevail above the emperor’s tyranny, married the men in secret anyway.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

When Claudius found out, St. Valentine (as well as the married soldiers) was promptly put to death.

The reality, however, was not quite as melodramatic. In fact, according to Ralph Mathisen, professor in LAS who specializes in Roman history, the details on the origin of Valentine’s Day are a foggy mess.

“We know nothing at all about the saints who were named Valentine except for their names,” he said. “And that’s why in 1969, the Roman Catholic Church took their names out of the official list of saints.”

So how did this elusive Saint (or Saints) Valentine become associated with love and romance?

“In the middle of February … there were two very popular Roman fertility cults,” Mathisen explained. “One was the Lupercalia, and one was the festival in honor of the goddess Juno, which was not about love or about romance; it was about big people making more little people.”

Lupercalia was a Pagan holiday celebrating fertility, as opposed to relationships and love. As part of the Feb. 13-15 celebration, according to History.com, women would place their names in a jar and be chosen by young, eligible bachelors as their true match.

But here is where the story changes (yet again).

“People in the Middle Ages didn’t want to talk about the nuts and bolts of reproduction, so (the Christians) made Valentine’s Day associated with romantic love,” Mathisen said, “which, after all, is intended to do the same thing, which is produce children. But (the holiday) has been kind of repackaged, if you will.”

As the decades passed, Valentine’s Day became less and less religious and more of a secular celebration in America. In the 1300s, people began celebrating it as a love-based holiday. In the 1800s and early 1900s, it challenged lovers’ poetry-writing skills — that is, until they could pay someone else to write the messages for them.

Thus, the greeting card was born. These popular paper messages have actually been around for decades. According to its website, Hallmark has been making holiday cards since 1910, with other similar companies following its lead.

Whether it is through American’s own sentimental messages or pre-written greetings, Valentine’s Day has brought people together around the country as well as here on campus.

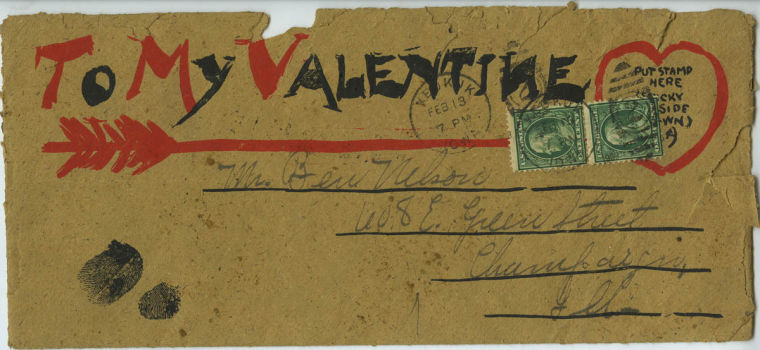

The University’s Student Life and Culture Archives contains thousands of documents, recording student life from as far back as 1810. Nestled among these historic texts and photos are a few early 1900s-era Valentine’s Day cards.

Benjamin Nelson was a 1911 alumnus of the University, graduating with an engineering degree. His archived scrapbooks contain documentation of his life as part of the Gamma Mu chapter of Sigma Nu, with correspondence to a certain unnamed lady friend. Identified only by her initials, N.I.T. belonged to Alpha Chi Omega and wrote “Benny” a heartfelt Valentine in 1908.

The Daily Illini has also documented students’ Valentine’s exchanges over the decades. A sincere Feb. 14, 1975, message on page 27 reads, “My darling Grinch — I love you more than life itself and all the onion pizzas in the world! Your Honey.”

So what has Valentine’s Day come to represent in this day and age — love? Chocolate? Onion pizzas?

“I think it represents people being in love and being able to express it,” said Mefah Joyner, sophomore in Media and Illini Media employee. “It gives people the excuse to set some time aside to appreciate their significant other.”

Sarah Richter, freshman in DGS, agrees that it is mainly centered upon people in relationships and their connections.

“It shows how much people care about each other,” she said.

Despite Valentine’s Day’s long, slightly dark and confusing history, the emotion-filled holiday is wildly popular today, and holds a somewhat charming significance in the eyes of many.

“Even over the course of nearly 2,000 years,” Mathisen said, “The basic message has stayed the same.”

Reema can be reached at [email protected].