Sochi Winter Olympics conclude while major LGBT issues continue

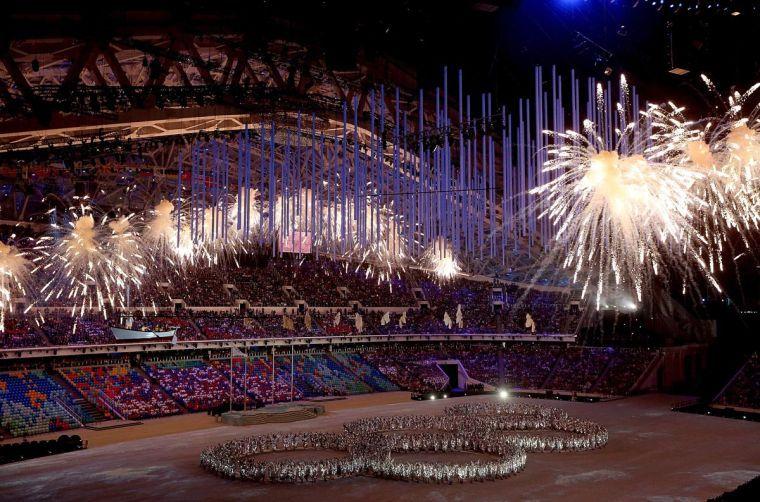

Performers in mirrored costumes form the Olympic rings under a fireworks display during the Closing Ceremony for the Winter Olympics at Fisht Olympic Stadium in Sochi, Russia, Friday, Feb. 7, 2014.

February 25, 2014

Under Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and a symphony of fireworks, International Olympic Committee president Thomas Bach passed the Olympic torch to Pyongyang’s mayor, as Bely Mishka, the polar bear Olympic mascot, blew out Sochi’s Olympic flame. And with it died the Olympic furor rife with geopolitics, bad hotel rooms and, most importantly, human rights dilemmas.

The games ended well for Russia. They ended up as leaders in both gold and total medals won. President Bach spoke to the world on Sunday as the Winter Olympics in Sochi were drawing to a close, and praised Russian President Vladimir Putin for hosting an “excellent” winter games and recognized “a new Russia … efficient and friendly, open to a new world.”

The Russians had never before hosted a winter Olympics, hosting only one summer Olympics as the now-defunct USSR.

When the location of the games was selected seven years ago, nobody expected a Russian history lesson. However, this is exactly what happened. The world wanted to give Russia a chance to showcase itself. This was an Olympic games run by a widely considered autocratic ruler with an agenda. This time around, the stubborn fifth Olympic ring opened after synchronized dancers glowed and teased the world.

There are currently no Russian laws that prohibit the discrimination of the LGBT community. In fact, laws passed in summer 2013 allow police officers to only arrest or detain tourists whom they suspect as being gay or suggestive of pro-gay propaganda. It was a winter games that promised something spectacular on the political spectrum.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

University Slavic languages and literature Professor Harriet L. Murav does not find these laws particularly startling.

“I think they’re not surprising, but that there is a particular history of intolerance that goes back to soviet times,” she said. “Liberalism in former soviet Russia doesn’t really mean the same thing that it does here.”

There had been a discontinuation of the gay rights discussion as the games went on, something that dissatisfied many human rights activists.

“NBC promised to give adequate coverage to the horrible situation LGBT Russians are facing, but so far little has aired during actual Olympic programming,” said Charles Joughin, a spokesman for the Human Rights Campaign based in Washington, in a story in The Washington Post.

The buildup to the games in Sochi were promising to garner political controversy ever since Putin passed numerous anti-gay laws back in summer 2013. In response, President Obama sent three openly gay athletes in the U.S. delegation for opening ceremonies – retired tennis icon Billie Jean King, two-time Olympic hockey medalist Caitlin Cahow and figure skating champion Brian Boitano. On the opening day of the Olympics, Google joined the fight by sporting a rainbow-colored doodle on its homepage with athletes as the letters.

In the beginning, there was subtle protestation. Germany fashioned rainbow uniforms for the opening ceremony. Canada and Sweden sponsored ads backing their gay athletes. Olympians, like figure skater Ashley Wagner, spoke out about human rights. Despite the furor, the scene died down as news channels that covered a majority of the games, like NBC, focused more on corruption, worker exploitation, run-down hotels, yellow tap water and geopolitics. There was no John Carlos moment of the 1968 Olympics. The movement fizzled out. And why not, right? A whopping 84 percent of Russians support Putin’s laws, according to a study done by The Washington Post.

However, Murav questions these polls and their accuracy.

“One survey by a western media outlet may not actually capture the complexity of responses to these issues efficiently,” he said. “I have a feeling the number is below 80 percent … you have to bear in mind that Russian citizens who are 50 years old or more are very sensitive to giving their true beliefs to poll takers because they grew up in soviet times where having the wrong opinion had consequences on your life. … In Russia generally anything that isn’t completely mainstream is fairly precarious.”

However accurate this figure may be, the issue hits home for many University students and LGBT community members.

“I think (these laws are) terrible … I think they’re a step back for the LGBT community,” said Elliot Cobb, freshman in FAA. “Well, I imagine it’s just something that’s engraved in them, in their culture. … I think it’s just kind of a shift the world needs … to be more accepting of the LGBT community.”

There were talks about the U.S. reciprocating what the Russian, then Soviet Union, government did in 1984 when it, along with 14 other allied countries, boycotted the Los Angeles Summer Olympic games at the height of the Cold War.

“It’s unfortunate that we chose to have the Olympics there and then the laws were passed,” Cobb said. “It creates this awkward conflict. Do we attend this? It’s hard for gay athletes and gay supporters to get there and … it just created a bad situation.”

Leslie Morrow, director of the University’s LGBT Resource Center, said she feels there is still progress to be made, finding the treatment of the LGBT community in Russia “archaic.”

“Obviously I find that it’s a human rights violation. Seeing that these laws are becoming more and more archaic and senseless, it doesn’t make sense to discriminate against someone based on sexual orientation, gender identity or expression,” Morrow said.

Jessica Ratchford, sophomore in Engineering, feels the anti-gay climate in Russia is in large part due to President Putin’s regime.

“They’re following a misguided ruler out of patriotism and loyalty to their country and just a lack of knowledge and understanding of their fellow citizens,” she said.

Perhaps it’s also out of fear, Morrow said. Members of the Russian punk rock group Pussy Riot were publicly flogged by Cossacks after performing a protest song in Sochi on Feb. 19.

“I think it’s really disheartening… It’s certainly presented as if it’s a united front,” Morrow said. “I remember them saying early on, ‘Oh, there are no gay people in Sochi.’ I think it’s ridiculous, and clearly there’s a climate that suppresses that fact, but the reality is (that) they are there, but it’s obviously not a safe place to be,” she said.

Ratchford believes these laws are a step back in the struggle for equality and human rights.

“These laws will be looked at (30 years from now) the same way as segregation laws are looked at,” she said. “It’ll be a part of history where we will look back and say, ‘That was a dark part of our time, we’re shameful and regretful.’”

Despite these facts, Ratchford has high hopes for the future.

“I hope that every time there’s discrimination against basic human rights that we learn to accept each other a little more and learn that just because we’re different that doesn’t make us any less human,” Ratchford said. “We should’ve learned it the first three times around, that sex doesn’t make us different, that race doesn’t make us different . . . maybe third times a charm.”

In 1936, the Nazis shocked the world as Berlin hosted the summer Olympics. The world temporarily turned a blind eye to Hitler’s anti-Semitic campaign. The rest was history.

Sunday night the curtains closed. The somber feeling of having to wait two years for another Olympics descended. The expensive games ended and the human rights issue haunting the games was effectively swept under the rug. The rest of the world looks forward.

Eliseo can be reached at [email protected].