Celebrating South African freedom at Krannert Center

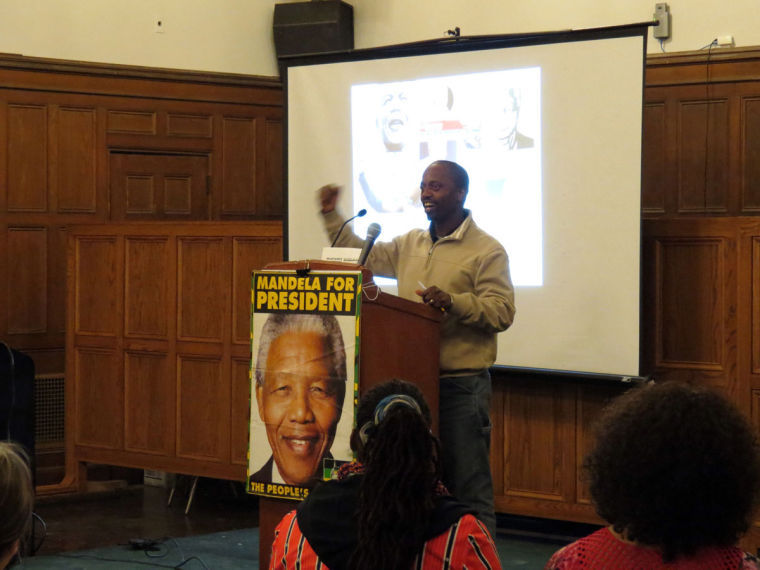

Mbhekiseni Madela gives a speech at the University’s Nelson Mandela memorial service in December 2013. Madela will be at the “A Celebration of South African Freedom Day” on Wednesday at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts.

April 23, 2014

For South Africans, 2014 marks 20 years since the general elections of 1994 that elected the late Nelson Mandela to office. As an anti-apartheid revolutionary, Mandela sought to bring human rights to all South Africans, regardless of color.

On Wednesday, Mandela’s efforts will be celebrated at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts through “A Celebration of South African Freedom Day,” an event that will focus on the role culture played in the liberation struggle. The event will take place from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. at the Tryon Festival Theater.

For Mbhekiseni Madela, a doctoral candidate in Education and a speaker at the program, everything has changed over the course of 20 years.

Madela, who is of Zulu descent, grew up in the Kwazulu Bantustan, or “black homeland,” an area geographically segregated from whites in South Africa.

“The general demographic of South Africa was predominantly black, but they were the ones that were ostracized and put in the periphery in some way,” Madela said.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The school systems were highly influenced by Apartheid thinking and were segregated not only by color, but also by ethnicity, he said.

“Every ethnic group had a university, and they were commonly referred to as ‘bush’ universities because they were the lowest standards ever,” he said. “The school system was like that, separated as a black child, you couldn’t go to a white school.”

In addition to the segregated school system, Madela was denied access to transportation, restrooms and public areas that were used by white people.

“That was normal,” Madela said. “You couldn’t question it because it was the order of the day … that was an experience of segregation and apartheid at it’s best.”

“Freedom now, Education later” was the motto in the schools, as uprisings were imminent throughout South Africa up to 1994, Madela said.

“Bantu education saw minimal resources, far inferior. If you would put a black child and a white child in the same grade at the time, you might even think the white child could teach the black child,” Madela said. “You had to educate a black person enough to be a servant of his master. That was the main principle.”

The anger Madela said he once felt prior to the South African general elections of 1994 has turned into forgiveness.

The dingy tenant homes his mother lived in as she worked the sugar cane fields to raise Madela and his two siblings in a 20th century sharecropping system are now vacant. The “Bush university” he got his bachelors degree from is now well-respected. And the democracy he never got a taste of 20 years ago seems as if it was always in place. The South Africa he knows today is much different than the one he knew back then, where riots, boycotts and violence were commonplace.

Madela has vivid memories of April 27, 1994, when the elections took place. With the check of a box, it all changed.

“The actual experience on its own was an incredible experience,” Madela said. “We couldn’t sleep. We’d go door-to-door, urging people to go out and vote because most of us were voting for the first time.”

When it was all said and done, Nelson Mandela had triumphed, and this change meant a lot to Madela.

“It meant a new world, it meant a new era, it meant new dreams .. you began to see the beauty of South Africa which you couldn’t see before because it was beautiful for some, and ugly for some,” he said.

Amongst whites, trusting a government run by black people was difficult, according to Madela.

“During those years— ‘95, ‘96 —predominantly white people bought candles, bought paraffin like never before because they were thinking ‘Let me have a standby in case electricity goes, because the black man can not handle to keep electricity,’” he said.

Madela feels many fled the country for the same reasons. A cultural movement was holding the reigns of the country in the meantime, with people maintaining unity through music and sports, he said.

“Sports has been the main catalyst in most cases … it was the main driving tool to facilitate reconciliation,” he said. “The more we began to see black athletes participate in a more inclusive way … it made this myth of reconciliation a reality.”

During the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, Madela volunteered as a driver for FIFA officials and referees. He saw it as a time for South Africa to showcase its progress. “World cup 2010 — that was the taste of Africa … it changed South Africa in the eyes of the world,” he said.

After he was offered an opportunity to work as a Zulu language instructor, Madela came to the states in 2010. He received his master of arts in African studies in 2012. Upon his arrival to the United States, he realized South African history wasn’t too dissimilar.

“I began to reflect and … with African Americans, we seem to have a very common history when it comes to apartheid, even though here it is not called apartheid. When you read and learn about this segregation in school .. it’s the same thing we went through,” Madela said.

This is a notion that Amira Davis, African American Studies faculty member and African beats musician who will perform at the event, agrees with as well.

“For me, it has always been important to connect the two struggles, that the enslavement of people of African descent in American have endured is closely related to the severed colonialism in South Africa and the system of apartheid that followed,” she said.

Davis is a part of a music group along with her daughters, who perform music of the African diaspora. They showcase routines from West Africa, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

“I’ve done this to show a Pan-African connection. I’ve done this to show (where) most people who are of African descent originated from.”

Davis started arts and education performances in Chicago over 30 years ago, and has also used the arts as a platform to advocate for the anti-apartheid movement.

For Davis, there is a huge purpose in her music.

“For me its always been about liberation, and to a certain extent, resistance of the culture that Europeans have placed on us, its about trying to reclaim that culture.”

For James Kilgore, lecturer in Global Studies, the event on Wednesday will also be one of significance.

“We decided to put together this event to expose the students to a little bit of African culture and in particular to look at the role arts and culture play in the struggles against apartheid. So students can not only (experience) the kinds of performance arts that we attain at Krannert Center but also the way ordinary people use music, poetry and other art forms for their political struggles,” Kilgore said.

Eliseo can be reached at [email protected].