New study re-examines the ‘just say no’ tactic in drug refusal skills training for adolescents

September 15, 2014

It was a girl that changed *Derrick’s life the night she introduced him to alcohol.

In high school, he was the kid that got mad at friends who used substances and often wondered why anyone would hang out with “that” crowd. He was “in the shell,” and a “loser,” as he described himself. Until he met *Anna. Against the odds, she was nice and successful. And she was a binge drinker. But she had a crush on Derrick and introduced him to a “whole new side of life.”

“She was using alcohol to get me drunk to hook up with me,” he said. “The first night was a few drinks. They put it in some gas station bottle and gave me a lot of random shit. They were all surprised, saying, ‘Derrick’s here! You go to parties? I didn’t know that!’”

His first kiss happened that night, and then his second, third, fourth. He started to like this new lifestyle.

“A few weeks later, a friend who was at that party texted me to ask if I was going to fly tonight,” Derrick said, meaning to get high. “I already drank so I might as well try smoking.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

He brought $5 as requested and went to the dealer’s place. They gave Derrick a pipe and then a bong and then a gas mask, something he didn’t know could even be used with drugs.

“I had a very good time that first time,” he said.

He graduated from high school a semester early and started renting his own apartment, becoming a “stoner” because he was the only one in his friend group without supervision. When he got accepted to the University, he decided he wanted to prove something to the world.

“I’m going to be the kid that can prove to other people that you can do a lot of drugs and still be successful,” he said.

For Derrick, no is not an option.

***

A new study co-authored by scholars at the University investigates teaching adolescents to “just say no” to drugs. Refusal skills training, techniques used to refuse drugs, may not be as effective as previously thought.

Social work professors Douglas Smith and Karen Tabb worked on replicating a study in which a group of African-American adults with alcohol problems showed they benefitted more from refusal skills training, a fact that surprised Smith.

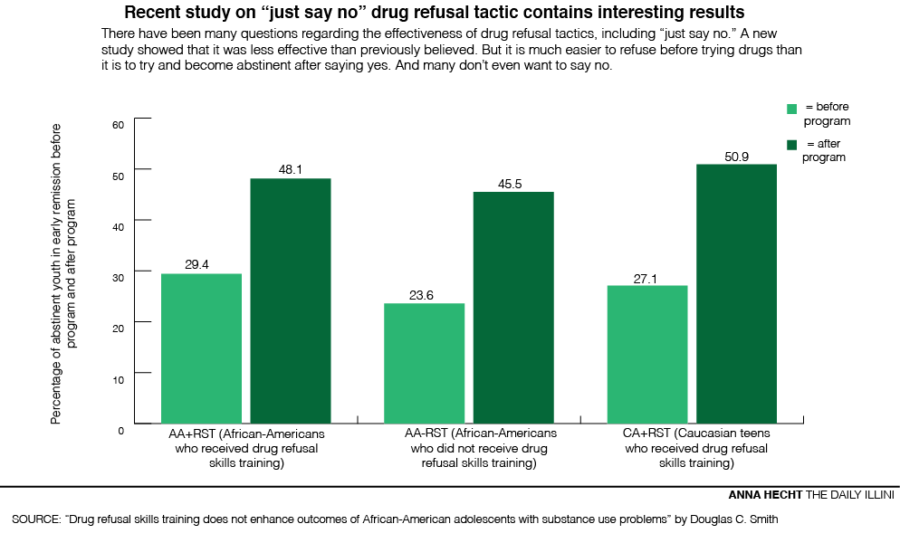

Smith and Tabb compared the results of 214 African-American adolescents who received refusal skills training with 212 African-American adolescents who did not. The study also looked at 214 Caucasian youths who received the training.

About 48 percent of the African-American teens who received the training were abstinent at follow-up whereas 45 percent who did not receive the training were not.

Roughly 51 percent of Caucasian teens were abstinent three to six months later.

“It’s not that just saying no isn’t effective, it’s that it’s not the magic bullet for improving treatment for minorities,” Smith said. “What was more important was how many of the different treatments did they get overall rather than did they just get the ‘just say no’ piece.”

The “just say no” motto began in the 1980’s and explained to children and adolescents that drugs are bad, Smith said. A well-organized program uses evidence-based therapies with research support that proves certain methods are more effective over others, Smith said. Programs that are not effective “do a little bit of everything” and may do activities that are unrelated to why patients are there.

“Programs that are evidence-based tend to be very focused on why you’re here,” Smith said.

These programs focus on key components and teach strategies to help users reach their goals.

***

Mary Russell, coordinator of the Alcohol and Other Drug Office, said that “just saying no” only emphasizes not getting started with drugs and does not help those that are already involved.

“It’s one thing to be able to stop using while you’re in treatment. It’s another thing to sustain that change when you return to your day-to-day life,” Russell said. “If you want to sustain abstinence, you have to be able to say, ‘Thanks, but I’m good.’”

Derrick has introduced 19 people to drugs, but said he always asks if they are comfortable and sure that they want to do it.

“It’s not a peer pressure thing, but with my core group of friends, sometimes I get that,” he said. “They’ll pass it to me and sometimes I won’t want to say, ‘No, I’m good,’ because they’ll push back.”

When the factor of money comes into play, Derrick said refusing free drugs becomes tricky.

“There is this weird, ‘Oh, I don’t want to turn down this bong,’ especially when I’m not paying for it. So sometimes I’ll take it and just get too high; I’ll have to go back to sleep,” he said.

Over time, it becomes harder to say no to drugs after the brain becomes used to the substance, Russell said. Even after going through treatment, people may still have the desire to use.

“They don’t say no because they want to say yes,” Russell said.

The settings in which users are raised also affects how they respond to drugs. Some people may have better access to resources to help them whereas some oppressed minority groups do not. Reasons for using, like numbing or avoiding the difficulties of life, can deter someone from quitting use, Russell said.

“If you’ve built a whole social life around using and now you’ve decided not to, it could seriously affect your social life and friendship circle,” Russell said. “Depending on the culture and group a person belongs to, there may be particular pressures on continuing relationships with these people.”

Derrick said pressuring people into doing drugs is not as common as it seems, but there is still a social pressure among friends.

“A friend who was too tired, I might’ve been like, ‘Oh, come on, join us,’ or something, but (peer pressuring) is definitely not that common,” he said. “Sometimes I’ll want to do a little bit, and I’ll get pulled into doing a lot.”

Russell said the key strategy is having the motivation to sustain resistance over time.

“Having access to support over time, even after you leave treatment, is really important,” she said. “Accessing educational information, clinical information, support services, building skills, talking to friends … all of these things in combination make a difference.”

Brittney can be reached at [email protected].