Eating bugs? Truth is, you may already be

January 26, 2015

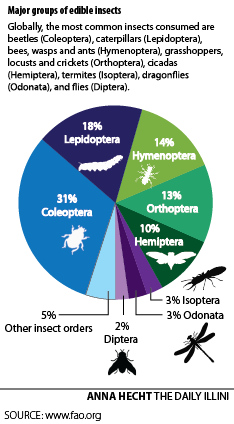

Bugs. Insects. Arthropods. Regardless of the terminology, these creepy, crawly critters wriggle their way into homes, end up splattered on windshields and can be found in the everyday foods people eat (within FDA standards). While many cringe at the idea of eating bugs, which is called “entomophagy,” this practice is widely accepted in many countries around the world. For students enrolled in Professor May Berenbaum’s Integrative Biology 109 course, “Insects and People,” eating insects during the course’s bug buffet lab is anything but accidental.

“Each semester, we hold a lab that is a bug-eating buffet where students can try different kinds of insects,” Berenbaum said. “It is endlessly fascinating to people, particularly if you take the geekiness out of it. We are not eating live stuff because nobody does that for real, but all around the world, people do not bat an eye at eating insects.”

Surprisingly, the idea of eating insects doesn’t seem to be an insurmountable problem for IB 109 students, either. Michelle Duennes, a Ph.D. candidate in Entomology and the IB 109 teaching assistant, said students often enter the class being “very afraid of insects and leave feeling much less afraid.” For students who have a fear of insects, Duennes said she tries to start them off with “something easy” in order to build and overcome their bug-eating confidence.

“We had a girl one semester who had a diagnosed fear of insects. She took the class to overcome her fear,” Duennes said. “It was a really big deal for her to put a mealworm in her mouth. She couldn’t really take it much further, but I think that really helped her a lot in overcoming those fears. And then, you have the students who are willing to try anything.”

This same open-minded attitude toward eating insects is one many entomologists wish more people would adopt. Both Duennes and Berenbaum, who was recently awarded the National Medal of Science, the nation’s highest honor in science achievement, recognize the many nutritional and environmental benefits of raising insects as an alternative to traditional livestock.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

In the U.S., for example, people are beginning to recognize that entomophagy is much more sustainable than eating other forms of animal flesh. According to Berenbaum, raising insects produces fewer green house gases and results in less competition over resources in terms of the amount of animal feed consumed. This is because insects are much more efficient in how they convert plant food into animal meat. In terms of nutritional value, Duennes points out that insects are a balanced source of sustenance for humans that help to meet unique nutritional needs around the world.

“If you think about all of the energy that goes into getting a beef product from a cow, and then compare that to the energy that goes into feeding an insect, it is just orders of magnitude larger than the energy and the time you would have to put into rearing an insect for eating,” Duennes said.

In recent years, there has been a lot more buzz surrounding entomophagy. This, according to Berenbaum, has largely to do with the ongoing concern over global food security. There is a strong push from countries, such as the Netherlands, that have invested millions of dollars in entomophagy research to find ways of mass producing insects for human consumption. Additionally, Berenbaum attributes the spread of entomophagy to globalization and the public’s newfound appreciation for novelty, variety and experimentation.

“In general, ‘foodies’ are more common than they used to be and global commerce has allowed us to sample the world’s diversity,” Berenbaum said. “Most people’s lives, up until this point, have involved not eating insects. So, it’s an adventure.”

The same holds true for Berenbaum’s students when it comes time for the bug buffet lab. After teaching the course for almost 25 years, Berenbaum said she has experienced a wide range of reactions from bug buffet participants, including last semester, when students even “took selfies” while tasting the bugs for the first time.

“I think we’ve made more progress than anytime in the last 35 years,” Berenbaum said. “There’s periodic interest, and it might just be because of the general cultural shift — the globalization of the eating experience. But, maybe … maybe this time, we have reached the perfect storm where attitudes have changed, the need is greater than ever, and maybe this is the moment for entomophagy to triumph.”

Anna can be reached at [email protected].