University alumnus reflects on his time at the 1965 Selma protests

March 16, 2015

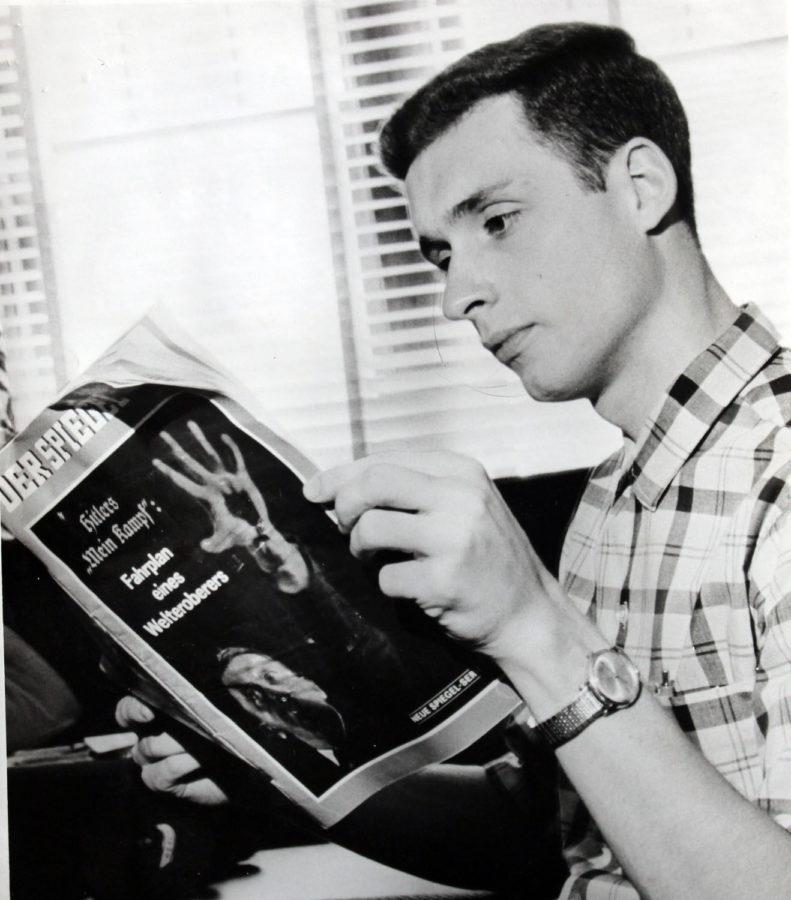

John Baird felt the edges of a large envelope.

He found it at his home buried in a box, wedged between newspaper front pages and term papers from his years at the University. The basement of his house in Decatur, Illinois, was his personal time capsule, and as he shuffled through its contents, he started to remember that day in 1965.

He still hears the sermon from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He remembers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge while the southern whites screamed, “Yankee trash, go home!” He remembers the blood, the sweat, the tears, but most importantly, the chance at a better life for African-Americans.

As his eyes scanned the title of the envelope, it all came back to him.

The engraving read “Selma.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

***

With the 50th anniversary of the protests in Selma on March 25, Baird was inspired to return to his past.

The campaign, led by King, started as a march through Selma, Alabama, as both whites and blacks used civil disobedience to fight for equal voting rights. Though facing violence and brutality from both police and southern whites in the process, the crowd finally arrived at the steps of the Alabama capitol — after 54 miles and five days.

Sundiata Cha-Jua, professor of history and African-American studies, said the Selma campaign was a pivotal moment for civil rights, leading to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“The campaign targeted voting rights because local activists and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King all believed voting rights would shift the power relations between African-Americans and Euro-Americans in the South,” Cha-Jua said. “They believed with the vote, blacks could gain control or leverage on law enforcement, criminal justice, city and county clerk offices and gain access to the better municipal services.”

The majority of the marchers were African-American. But dispersed throughout, whites like John Baird felt called to fight for equal rights as well.

***

Baird was a rare case. He didn’t follow the segregation customs.

His parents frequently spent evenings with another African-American family. His mother kept a book about the Montgomery Bus Boycott on one of her shelves. The pastor of his church in Decatur picketed in front of the courthouse in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, for equal voting rights.

While he was a student at the University in 1965, he heard that the McKinley Foundation was taking a group down to the next march in Selma.

His childhood, his family and his pastor taught him that it was the right thing to do.

“Anyone who has any sense of fairness and justice at all sees that equal rights are the right thing. Our constitution says all men are created equal,” Baird said. “It was accepted, just the way things are. If you don’t have someone telling you that it’s wrong, it’s just easy to go along with the way things are.”

***

When Baird and four other students started their drive to Selma, he said they were scared. Not only did they have friends who were arrested, but they read stories about two white men who were murdered for protesting.

Baird said he feared the whites more than the blacks in the south.

“I was afraid of the white community,” he said. “If someone found us five young people with Illinois license plates driving toward the south in Alabama, they could’ve rear-ended us or driven us off the road and kill us. There was history of whites in the south killing northern whites.”

However, they were welcomed with hospitality when they entered the home of a widowed African-American woman in Selma.

“The lady was just lovely. It’s just what you expect nice people to be like. We felt comfortable; it was like being with a friend,” Baird said. “She was probably surprised that we were kind to her. She may not have known many white people smiled at her and thanked her and treated her as a human being.”

With music playing, the black community members of Selma filled their dinner plates with grits, mashed potatoes and fried chicken. Baird and his group were thanked tremendously for their efforts at the dinner.

“This is my country, the country I’m going to live in for the rest of my life. I want to live in a country where people have hope, where people are not bitter,” Baird said. “I don’t want to live in a country where the black community is bitter toward the white community. I want my life to be a statement of promoting justice and fairness and peace.”

But a day later, they attended a church ceremony, where King preached before they started the march.

“I was thinking this is huge national event, and I’m here. I’m part of it. It was thrilling,” Baird said. “The words I don’t remember, but it was moving, reassuring and encouraging that we are doing the right thing, and the lord will protect us.”

During the sermon, helicopters swarmed above. National Guardsmen with carbine rifles surrounded the perimeter. Baird will never forget the hope in everyone’s eyes as they realized the nation finally cared.

But now, he sees one of the most hurtful parts of that day more clearly: the harassment as they stepped onto the bridge.

One spit in a marcher’s camera lens, others called the northerners white trash as they walked in the crowd.

Although he didn’t do anything about it at the time, he knows how he would respond today.

“If I had a chance to talk to those white people at the side of the road, they would see that I’m like them in most ways. We’ve all hurt when a loved one dies; we’ve all loved our children and we bleed when we get hurt. We are people, and we could connect on so many good levels,” Baird said. “It’s just too bad that there’s this wedge between us.”

Baird left for the University before the crowd reached Montgomery, but Mary McCreary, another University student who traveled in the group, stayed. Standing in an ocean of people, she said she had never seen so many people congregated for one purpose.

“You felt powerful because you were one of many, but as you look at yourself as one, you felt insignificant. That was what really hit me, look what we can do when we combine our efforts,” McCreary said. “I am so proud that I had the opportunity to go and help in that way. To help change history somewhat and to be a part of something that so many people believed in, acted on and marched for. It was the chance of a lifetime.”

***

As Baird reread the title of the envelope, holding news clips and published magazine photos from Selma, he saw the progress the U.S. has made.

“My experience in Selma gave me hope to know that there are thousands of people who believe in human dignity, fairness and justice,” Baird said. “Progress was made. It’s an example that people can get together at grassroot levels, and we can make change happen. And we need to do that as much as ever.”

At the 50th anniversary, though, he said he believes returning to this past and learning about its purpose is crucial. While he expressed concerns about racial equality in the U.S. today, citing the events of Ferguson, Baird said it’s the unity that he saw at Selma that gives him hope.

“It’s going to take a lot of struggle and a larger portion of our citizens stepping and speaking out to make that happen. People have to not be focused on their own life and personal interests,” he said. “People need to stand up for what’s right. We all have a responsibility for speaking out and guaranteeing that the United States of America needs us all to work toward promoting a better country with more justice, fairness and peace.”