LGBTQ representation evolves in film

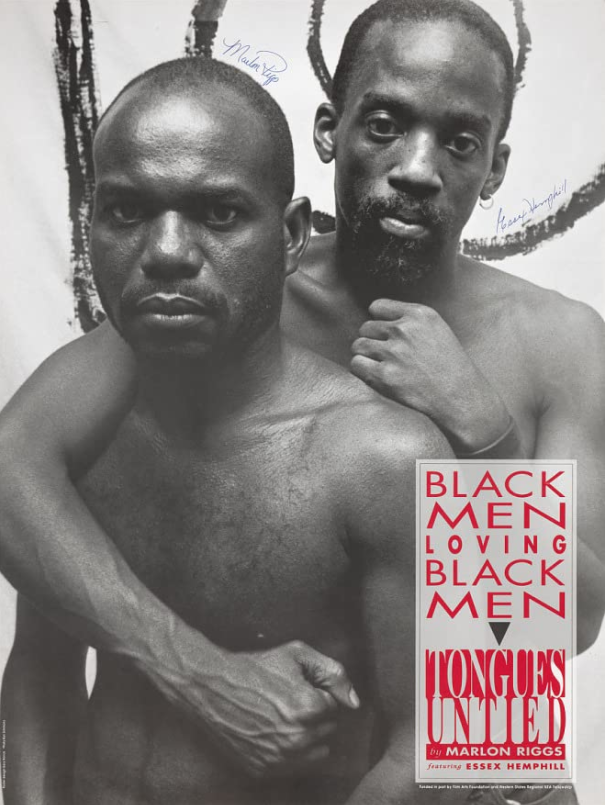

The cover for the movie “Tongues Untied” is pictured above. The film was released in July 1989 and was one of several LBGTQ movies produced by Marlon Riggs.

February 11, 2021

Although the amount of LGBTQ+ representation in films has grown in recent years, the LGBTQ+ community’s portrayals have always existed within movies. The history of LGBTQ+ representation in films is far from short.

From the ‘30s to the ‘60s to the ‘80s to 2021, LGBTQ+ representation in film has evolved from subtle hints of gay characters to full-blown movies surrounding the lives and experiences of LGBTQ+ people.

In 1930, the Motion Picture Association of America adopted the Motion Picture Production Code, known as the Hays Code, to censor portrayals of sexual perversion or deviance in the film industry. While the Code never explicitly banned homosexuality, it was universally assumed homosexuality was forbidden.

In the 1940s, a budding culture of the experimental, avant-garde film was created by gay artists, such as Kenneth Anger, Gregory Markopoulous and Curtis Harrington, according to freelance blogger Daryl Chin.

“These films were created without the support of commercial movie studios, and these independent, low-budget films often portrayed themes that were thought of as too controversial for mainstream cinema,” Chin said.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

“By the 1960s, this experimental film culture became known as ‘underground film,’” Chin said. “This culture was influential in creating a theme of homoeroticism that would eventually be reproduced in mainstream commercial films.”

In 1968, the Hays Code was replaced by the MPAA film rating system, a voluntary rating system created to help parents determine what films are appropriate for their children.

“In the 1970s and 1980s, gay and lesbian film festivals emerged, which created a space for an audience consumption of LGBTQ+ characters and stories,” Chin said. “During this time, gay and lesbian filmmakers began experimenting with narrative form.”

“During the AIDS crisis, the accessibility of video provided gay and lesbian artists of color a platform for their films,” Chin said.

Some of these artists were Marlon Riggs, who produced, directed and wrote documentary films such as “Ethnic Notions” and “Tongues United”; Shari Frilot, who directed “Fly Boy” and “Black Nations/Queer Nations”; and Cheryl Dunye, who produced the experimental documentary “Janine” and the narrative short film “Greetings from Africa.”

In 1992, B. Ruby Rich, a film scholar and LGBTQ+ activist, christened the term “New Queer Cinema” to describe the increasing prevalence of independent LGBTQ+ films in the early 1990s.

Chin said the New Queer Cinema genre opened the doors for young, LGBTQ+ American filmmakers to share a post-Stonewall openness to questions of gay identity and politics.

In Michele Aaron’s “New Queer Cinema: An Introduction,” Aaron said films from the New Queer Cinema era shed light on the voices of the gay and lesbian community and of the sub-groups within the community, such as the experiences of LGBTQ+ people of color.

Aaron said New Queer Cinema increased Hollywood’s awareness of LGBTQ+ audiences. Still, it created little-to-no change in cinematic LGBTQ+ representation because the film industry appropriated and diminished LGBTQ+ issues.

“An upside to Hollywood’s appropriation of the new LGBTQ+ potential of cinematic storytelling was the budding acceptability of mainstream display and circulation of LGBTQ+ characters and themes,” Aaron said.

Since the early 2000s, there has been an increase in LGBTQ+ films and the popularization of LGBTQ+ films.

From “Milk” to “The Kids Are All Right” to “Pariah” to “Moonlight” to “Call Me By Your Name” to “Happiest Season,” it’s safe to say LGBTQ+ films have gained a more secure footing in the film industry.

While LGBTQ+ representation in film has come a long way since the 1930s, there is still a lack of cinematic representation for LGBTQ+ people of color and LGBTQ+ people with disabilities, according to the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, known as GLAAD.

The 2020 GLAAD Studio Responsibility Index, a report that tracks the quantity, quality and diversity of LGBTQ+ characters in movies released from major studios during 2019, found that only 22 films out of 118 films included LGBTQ+ characters.

The Responsibility Index found that the racial diversity of LGBTQ+ characters saw a significant decrease in 2019, with 34% of LGBTQ+ characters being people of color, compared to 42% in 2018. Out of 50 characters in 2019, 33 were white people, 11 were black people, four were Latino and two were Asian/Pacific Islander.

In 2019, there was only one LGBTQ+ character with a disability in major movie releases.

Although the amount of LGBTQ+ characters has increased in mainstream commercial films, the film industry still struggles with including LGBTQ+ characters in movies, especially including LGBTQ+ characters of color.