Rating: 8.7/10

Sometimes, a player can’t predict a move before the inevitable falls upon them. Anticipation is lost, and frustration grows anew. “Checkmate” is what they call it when the opponent threatens the king with capture. The chessboard is inescapable from this loss.

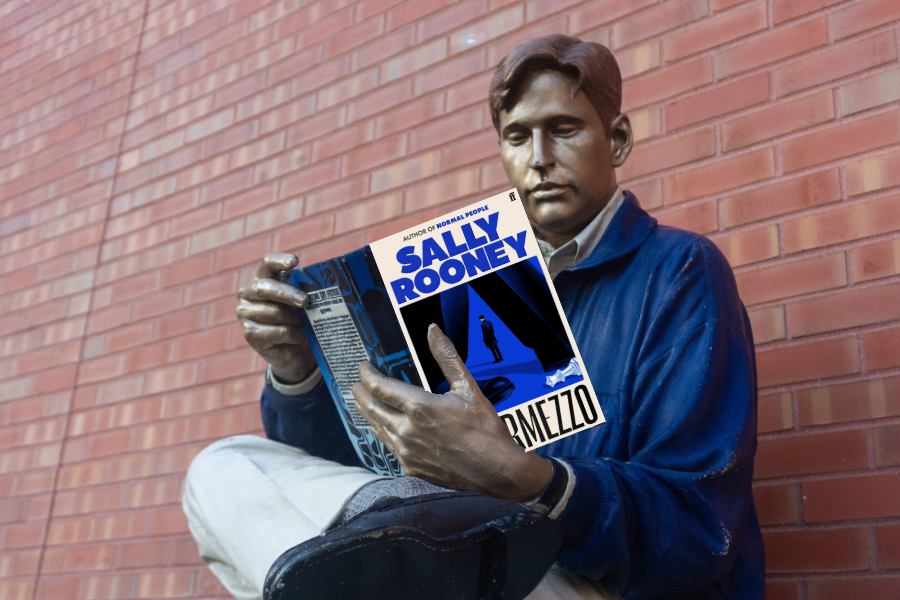

That’s where the story begins in Sally Rooney’s latest novel, “Intermezzo.”

Published on Sept. 24, 2024, the 454-page novel is yet another undeniably evocative work of prose from Rooney. It follows the insurmountable grief of two brothers after their father’s death, questioning the morally righteous in a seemingly cruelly corrupted reality. And Rooney’s no stranger to intensely riveting works of art.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

In her previous novels — “Conversations with Friends” (2017), “Normal People” (2018) and “Beautiful World, Where Are You” (2021) — Rooney is known for illustrating characters who desire emotional intimacy above all. In this case, no matter at its worst or best, love is the “chessboard” that follows loss, checkered with various players of contrasting pasts playing toward a common goal: win.

A winner is what Ivan Koubek is known as in the competitive chess world, or, at least, he once was and regarded himself as so. He’s faltered from the rankings after losing his father, and the geeky 22-year-old, with bitten nails and braces to align with his social awkwardness, materializes upon the pages.

His brother, Peter, is quite the opposite. In his 30s, Peter outwardly encapsulates that of the trailblazing lawyer: successful and sophisticated without fear of being proven incorrect. But what he fears most may be the wretchedness of it all, inhaling alcohol and drugs and engrossing himself in work.

Their father’s death intertwines with the brothers’ romantic liaisons. Ivan meets Margaret, a 36-year-old arts program director, at his first chess event of the novel. They become consumed with one another despite the soon-to-be divorcée’s initial worries about the ever-looming age gap and the public’s response to the relationship.

But for Ivan, Margaret embodies “the kind of woman he believed he couldn’t have.” Never before did he feel he could want someone the way they’d want him; never before would someone utter, “It was perfect.”

Although 10 years older than his brother, Peter’s romantic life resembles the cliché love triangle — or so Rooney makes you think. Conventionality is never the point of her narratives.

The 32-year-old is caught between Sylvia, his college girlfriend who broke up with him six years earlier after a car accident, and Naomi, a 23-year-old college student who represents the lustful youth and portrays the object of men’s sexual desires.

However, the brothers’ love stories rarely meet on the board. They’re separated due to the unpredictable nature of their relationships and the fact their relationship isn’t what it once was.

Battling not only the loss of their father but the loss of each other and how they believed the world to work is excruciatingly unending, especially from Peter’s point of view. Although a problematic character with countless faults, Rooney makes him effortlessly human, possessing thoughts and ideals seldom addressed by society yet overly haunting for an individual.

“Thought rises calmly to the surface of his mind: I wish I was dead,” Peter thought to himself. “Same as everyone sometimes surely. Idea occurs, that is. Remembering something embarrassing you did years ago and abruptly you think: that’s it, I’m going to kill myself. Except in his case, the embarrassing thing is his life.”

Ivan instead contemplates the idea of an overarching power, not necessarily believing in God but finding the beauty in what he once deemed a meaningless existence.

“But I don’t think it means there’s nothing there,” Ivan said to Margaret. “Some kind of order in the universe, at least. I do feel that sometimes. Listening to certain music, or looking at art. Even playing chess, although that might sound weird … To me, it seems like it might all be related. Like, I don’t know, to find beauty in life, maybe it’s related to right and wrong.”

Despite a plot heavily focused on love, the bond worth noting is the one between the two brothers. After an attempt toward reconnection that ended in a repulsively hypocritical argument years in the making, it remains unclear whether this pent-up hatred will again lead to the childlike affection that once prospered.

What’s unnaturally stunning about this narrative is how Rooney’s mind works in developing two disparate characters. In Peter’s perspective, sentences are clipped, lacking a subject or verb; at times, there’s only a trailing thought difficult to follow. Ivan’s is filled with ceaseless sentences, whether in his mind or spoken aloud — the epitome of painfully awkward.

There’s not much that Rooney can’t do, especially within the last 20 pages. There, she barrels through the minds and souls of her readers, portraying an image of forgiveness between two halves divided from the same whole.

Although not interlaced into a taut knot, the ending is reminiscent of other works by Rooney: leaving the past behind and moving oneself toward the impending future.

“It doesn’t always work, but I do my best,” Peter thought to himself. “See what happens. Go on in any case living.”

It’s an unorthodox story that leaves one questioning the conventionality of life itself, but it’s also a story about love — something each character attempts to capture despite the flaws played throughout the game.