“The Boy and the Heron,” the latest film from Japanese auteur Hayao Miyazaki, is every bit as gorgeous and magical as many of the director’s incredibly symbolic films.

His first since “The Wind Rises” a decade ago, this film similarly feels like the director looking back on his own legacy and impact to a staggering effect.

Miyazaki, the director of Studio Ghibli, has earned a strong reputation for his painstakingly beautiful hand-drawn animation and painted environments alongside his dazzling dream-like narratives. “The Boy and the Heron” is no different, further cementing Miyazaki as a world class talent.

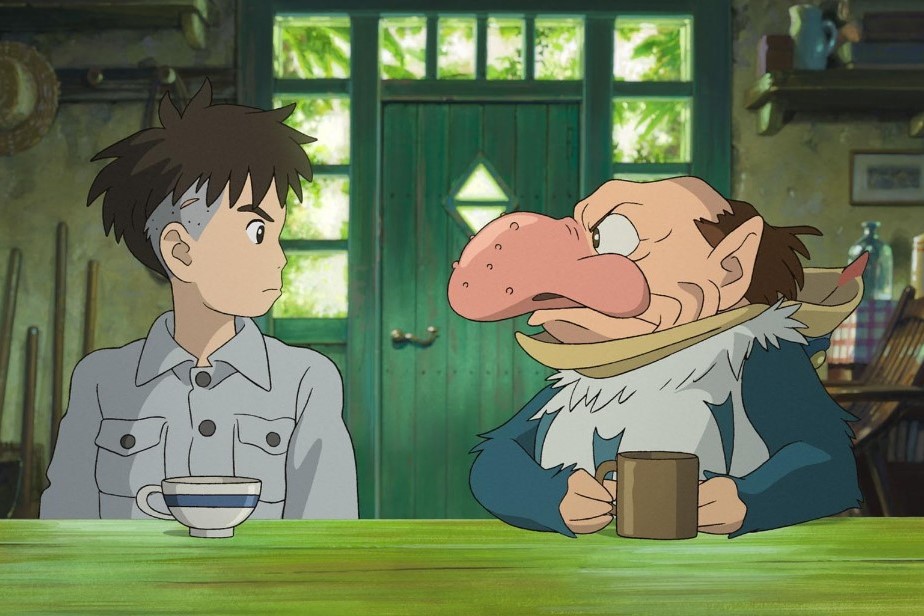

The film follows Mahito (Soma Santoki in the original Japanese cast), a boy growing up in the 1940s during the war after losing his mother in a hospital fire.

At his new house, Mahito starts to see strange visions of a talking Grey Heron (Masaki Suda) who claims he can bring Mahito back to his mother. When Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), Mahito’s aunt-turned-stepmother, suddenly vanishes one day, Mahito finds himself embarking on a strange and metaphysical journey through different worlds in order to bring her back.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

The film was notable for a unique release strategy. Released July 14 in Japan, the film received no marketing. No still images from the film or trailers were shared and only minimal information of the plot was given, leaving audiences to enter the theater with no expectations.

Since the initial release, stills and trailers have been distributed, yet the narrative of the film was still unknown in the United States. This works to the film’s advantage, as the movie hits harder the less you know about it going in.

It’s not that there is some seismic twist or reveal. Rather, absorbing the minute elements of the world, taking in Miyazaki’s character-building and watching everything come together as the film reaches its climax is incredibly gratifying.

The animation — as expected — is excellent. The motion is slick and expressive while all the character and background designs are unique and delightful. The painted quality to the scenery and environments is rich and dynamic.

The animation’s colors are harmonic. The way in which golden and gray tinted clouds float atop endless waves of earthly greens, browns and blues intermixed with pops of reds and pinks from flowers and features is eye-catching in the truest sense. Ghibli movies are characteristic for creating these worlds that you want to live in — “The Boy and the Heron” is no exception.

One has to talk about the creatures when discussing a Ghibli movie. The heron swerves from creepy to comic, while “warawaras,” little round white creatures with two black dots for eyes and a smile, are adorable in a classic Ghibli way. These creatures also bring about many of the film’s funny scenes and segments in a way that never feels grating or overdone.

Joe Hisaishi’s scoring of “The Boy and the Heron” is one of 2023 cinema’s best. Orchestral and epic while feeling so intimate and bright, the soundtrack adds an extra degree of personality to the film while also giving the film’s sweeping emotional scenes that little something that binds it all together.

The english language dubbing is another strong point of the movie. The performances, including Robert Pattinson as the Heron and Christian Bale as the father, are all organic to the point where the dubbing often feels unnoticeable. Luca Padovan as Mahito anchors the entire film splendidly.

Miyazaki, at 82 years old, has claimed that he wants to continue directing films. Nevertheless, much of the context around this film involved potentially viewing it as the director’s swan song. To that end, the film is transcendent.

The design of the film is so prototypical when compared to the director’s earlier works. Mahito in many ways reflects the typical Miyazaki protagonist; a kid under a specific or tragic circumstance who, by interacting and overcoming struggle within a fantastical world, learns what is important to them and how to grow up.

Through these protagonists, especially Mahito, Miyazaki argues that to live is to find passion and cherish relationships with the people we care about.

Much like “The Wind Rises,” the film feels incredibly reflective. It’s almost like Miyazaki is looking back at a long and successful career wondering how much of it was any good, questioning whether someone should succeed him after he is done or if the entire operation should shut down all together.

It does not feel like that in the egotistical sense. Miyazaki is looking at the next era of Studio Ghibli, arguing that none of them can truly be happy trying to be the next Hayao Miyazaki.

It is an incredibly layered and poignant outlook that reinforces the film’s themes of learning how to change and come to terms with grief.

However, as the film operates on dream logic, much of this interpretation is simply that — interpretation. Miyazaki foregrounds atmosphere and mood over plotting, weaving in and out between the real world, the dream-like world and whatever is in between cuts themselves.

The result is at times inscrutable and hard to follow. Moreover, this dream logic makes it so that it can be hard to connect between what is happening on the frame and what the film wants us to think is happening.

To that end, this movie feels less accessible than many of Miyazaki’s earlier works. However, those that connect to the film on its transient plane of vibes and emotions can ultimately discover something that feels fully formed.

Though the sheer craft on screen is worth the price of the ticket alone, viewers should be aware that the film doesn’t answer many of the questions it poses. It forces the viewer to look at the film in their own unique way.

If “The Boy and the Heron” really is Miyazaki’s last movie, he would have gone out with a masterpiece. The film is deeply moving, wildly imaginative and beautifully made. It’s a work of art that adds on to Studio Ghibli’s vast and accomplished history in its own special and powerful way.