What America has failed to hear

A Year of Racial and Political Division: Where do we go now?

November 19, 2020

A Movement Re-Ignited

Shootings. Protests. Riots. A movement ignited.

Eight months. Over 250 days.

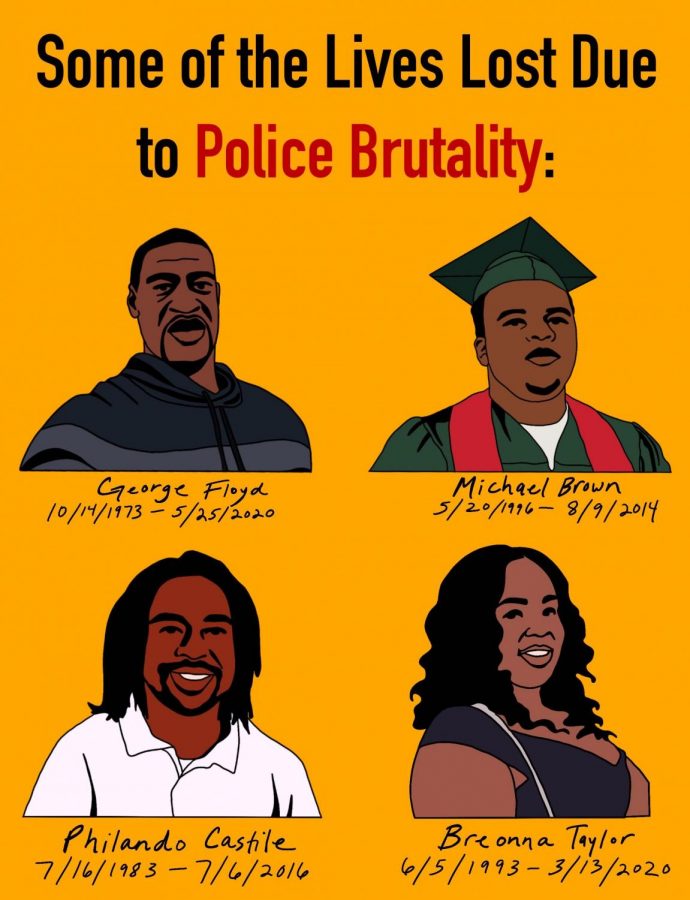

That’s how much time has passed since Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old emergency room technician from Louisville, Kentucky, was fatally shot by police officers executing a no-knock warrant in her apartment.

One of the officers, Brett Hankison, was fired on June 23, over three months after Taylor’s death. The other two officers involved — Jon Mattingly and Myles Cosgrove — were placed on administrative reassignment.

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Not one of them has faced criminal charges, but hundreds who have protested in response to Taylor’s death have been arrested instead. A grand jury did not charge any of the police officers with Breonna Taylor’s killing, though one former detective was indicted for “recklessly firing” into a neighboring apartment during the raid, according to a New York Times article.

A Change.org petition, started by law student Loralei HoJay, is calling for the arrest of the three officers involved in the case. It addresses President Donald Trump, Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear, state Attorney General Daniel Cameron and others. The petition has garnered over 10 million signatures, the second-highest amount in history.

Seventy-three days — two-and-a-half months — after the death of Breonna Taylor, another name was added to the list of Black people killed by the police.

“Please.”

“Mama.”

“I can’t breathe,” George Floyd — a 46-year-old Black man — begged at least 16 times.

“My stomach hurts, my neck hurts, everything hurts,” he told the four Minneapolis police officers — only to be told, “You are talking fine.”

On March 25, Floyd was killed at the hands of a white police officer who knelt on his neck for almost 9 minutes. The arrest was for allegedly using a counterfeit $20 bill. His death sparked a national outcry for justice. The petition garnered over 19 million signatures — the highest in history.

Decades of damage

It is more than the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd that have incited hundreds of marches and protests in all 50 states. It’s more than just the deaths of Ahmed Arbery, Emmett Till, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, Pamela Turner, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Walter Scott, Korryn Gaines, Alton Sterling, Atatiana Jefferson, Stephon Clark, Shantel Davis, Philando Castile and the many others who have lost their lives due to their complexion. It is more than these individual killings, but rather the collective of Black people who have been killed for hundreds of years due to the color of their skin.

These deaths are one of the many products of the systemic racism that has been woven into the fabric of the United States. The systems of society — the economy, education, health care, criminal justice — are infused with the inherent racism in which they were created and maintained.

Institutional racism — also known as systemic racism — is racism that is embedded into the organizations and power structures. The term was first used in Black Power: The Politics of Liberation by Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton in 1967. They wrote that institutional racism is less perceptible than individual racism because of its “less overt, far more subtle” nature, stating institutional racism also “originates in the operation of established and respected forces in the society and thus receives far less public condemnation.” This institutionalized racism in society leads to discrimination in criminal justice, employment, housing, health care, political power and education, which supports the continued unfair advantage to some people and disadvantage or harmful treatment towards others based on race.

Systemic racism in COVID-19, healthcare

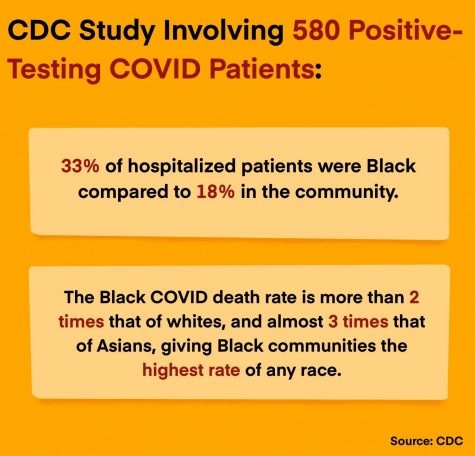

Institutional racism has been specially brought to light during the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the past several months, COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted Black, Latinx and other minority groups regarding the number of cases and death rates.

An article from the University of Minnesota highlights several studies that depict the health disparities revealed by COVID-19, stating COVID-19 rates are elevated in minority populations. A study group in the JAMA Network Open commented on two of the studies.

“The elevated incidence of COVID-19 among Black and Hispanic communities, largely attributable to social and structural vulnerabilities, seems to drive the differences in mortality among Black, Hispanic and white populations,” they wrote. “In short, rather than validating long-debunked hypotheses about intrinsic biological susceptibilities among non-white racial groups, the evidence to date reaffirms that structural racism is a critical driving force behind COVID-19 disparities.”

A report updated on July 24 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed the increased case and death rates among minorities. The data shows the American Indian, Black and Hispanic populations’ case rates are 2.8, 2.6 and 2.8 times higher, respectively than the case rate of the white population. Their hospitalization rates are 5.3, 4.7 and 4.6 times higher, and death rates are 1.4, 2.1 and 1.1 times higher, respectively.

The study discusses that discrimination, limited healthcare access, occupation, income, socioeconomic disparities and housing conditions are several factors that have put racial and ethnic minority groups at a higher risk for contracting and dying from COVID-19.

Dr. Jennifer Lincoln from Portland, Oregon, declared in her viral TikTok that these health disparities and implicit biases against minority populations are not new. She shared the prevailing biases among medical professionals about the Black population’s ability to feel pain. She stated that “50% of medical students and residents thought that Black people couldn’t feel pain the same way because their skin was thicker or their nerves didn’t work the same way.” As absurd as this may sound, it is a prevalent perception in healthcare and is a threat to the well-being of all Black patients, as they are less likely to receive adequate pain medications, will have longer waiting room times and are less likely to be taken seriously in hospitals and doctors offices.

LaShyra “Lash” Nolen further discusses in her Twitter thread the many examples of institutional racism in medical education, specifically physical exams. Dozens of medical conditions require a physical exam for diagnosis, yet the majority of medical material does not discuss how these physical signs appear on Black skin, even when certain conditions disproportionately affect Black and Latinx people.

Fortunately, Malone Mukwende, a 20-year-old medical student at St. George’s University of London is combating this lack of medical material by taking action against this disparity in medical education, according to an article in the Washington Post.