Illinois Commitment: What are you really committing to?

Crowds gather on the main quad to enjoy the weather during Mom’s Weekend on April 6, 2019.

July 15, 2020

The housing spiral burst and the economy was in a downward spiral, leaving many in a devastating financial situation; Max Williams was in elementary school when both parents lost their jobs during the Great Recession. With his mom a secretary and his dad a welder, they would work odd jobs to get by in their hometown LaSalle. Despite money being tight at home, Williams’ parents told him his only job was to be a student.

Today, Williams is a freshman in LAS at the University. Although his parents have found work again — his dad in welding and his mom in retail — Williams is among the first class to receive aid from the University under the new Illinois Commitment program.

Introduced for the first time this past fall, Illinois Commitment is a financial aid program that covers tuition for Illinois freshmen and transfer students whose family’s annual income is $61,000 or less for up to eight semesters. However, the cap for the 2020–2021 school year has increased to $67,100. The increase came after discussions between University officials and Gov. J.B. Pritzker, according to University spokesperson Robin Kaler in an email.

In its premier year, the program attracted students from the state’s largest city, Chicago, to more rural regions of the state, like LaSalle county. According to Provost Kevin Pitts, 31.4% of freshmen and transfer students were awarded Illinois Commitment.

“I probably wouldn’t even (have applied) to U of I if it wasn’t for commitment,” Williams said. “U of I was still the cheapest school for me so I was still really happy to get in and because of how good of a school it is.”

Get The Daily Illini in your inbox!

Illinois Commitment is not the only financial aid program the University offers. Illinois Promise, which has been around since 2005, covers tuition and fees as well as housing for families whose FAFSA form shows an expected family contribution of $0. Illinois Commitment is automatic for families whose income is below the threshold.

There are several ways to qualify for $0 EFC under FAFSA’s formula. A household income of $26,000 or less qualifies for $0 EFC, and families have to use federal assistance programs like SNAP.

The cutoffs for these programs are strictly enforced. Williams knows this firsthand: His family income was just above the threshold for Illinois Promise. He’s had to take out $15,000 in loans just to pay for housing.

Williams noted one of his frustrations with Illinois Promise and Illinois Commitment is the harsh cutoff for each program.

“I think there should be a gradual thing, (so that you can) kind of work your way up so you only have to pay a little bit based on how close you are,” Williams said. “(Illinois) Commitment doesn’t really cover your entire tuition like it says it does. It just covers what’s left after the rest of the grant money.”

The University wants students to know about all the financial aid it offers, so it embarked on a massive advertising campaign last year.

However, despite Illinois Commitment, the University often isn’t cheaper than other in-state schools. Using the cost of attendance calculator for both Illinois and Western Illinois (with a default income of $45,000 and $10,000 in assets), and Western came out to $2,162. Illinois’s was $17,481.

The University makes it seem like they offer ample aid, and that’s how they market Illinois Commitment. Williams was not alone in his concerns about the marketing of the Illinois Commitment program.

“I wish (they) would have been more clear about it because I thought it was like no matter what your FAFSA was, it was free tuition and fees,” said Marie Jensen, a freshman in Education. She is part of the Marching Illini and also received Illinois Commitment.

Like many high school seniors, Jensen was weighing her options and looking at other schools before committing to Illinois. She had a scholarship offer to play golf at Eastern Illinois but Illinois Commitment swayed her decision to turn down the offer. Despite the fact that Jensen’s cost of attendance at Eastern Illinois was a third of the cost of attendance at Illinois, she came to Illinois. The school’s background sealed the deal.

Jensen’s parents are divorced and her father lives in a town nearby her. Her mother has been the family’s sole breadwinner, but she recently started working a new job. Jensen estimates her mother’s income will increase to $67,000. Prior to the new cutoff, Jensen thought she would lose Illinois Commitment later in her time at Illinois.

“I really liked just the history of the campus,” Jensen said. “Knowing all the great people that went here, everything that they’ve done.”

Thankfully, Jensen does not have to take out loans this year. Jensen is majoring in Germanic Studies, hoping to become a German teacher, and she received local scholarships as well as the Golden Apple award, which provides training and financial support for future teachers. She does anticipate having to take out loans in the future, though, as her family’s financial situation might change.

Also in the College of Education, freshman Jailysse Delgado is an Illinois Promise recipient. Delgado is studying to become an English teacher and credits her educators for her career decision, but ultimately prioritizes happiness in her career.

“For me, I know that money is not what makes me happy, because I’ve been poor before,” she said.

For Illinois Promise, housing and tuition are covered. Delgado’s main expense at Illinois so far has been textbooks, but various expenses like going out, come up as well. Illinois Promise has been around since 2005, but despite its well-established history, Delgado felt she didn’t know everything about the program; for example, she said she didn’t know that Illinois Promise covered Private Certified Housing. Other students also wish the University took a more holistic approach when it comes to Illinois Commitment.

Illinois Promise is just one financial aid program that the University offers. Because of its novelty, Illinois Commitment might be the more famous one, but both programs shape student decisions to enroll at Illinois.

Nicole and Anna Rataj, twin sisters from Bartlett, Illinois, decided to attend the University after learning they were eligible for Commitment.

The Ratajs’ mother is the sole breadwinner in their household. Their mother owns a medical billing company, so her income varies by $5,000–$10,000 a year. Anna, freshman in LAS, said, “it’s just really a period of flux right now.”

Nicole, also a freshman in LAS, thought that the program was logistically straightforward and didn’t feel like she had to jump through a lot of hoops to get her financial aid. She felt, though, it does not adequately address the “middle-class squeeze,” where families make too much to get significant financial aid but not enough to pay all the out-of-pocket costs associated with a college degree.

“Maybe raising the annual income, because I know a lot of people in that range, a little bit above the cutoff (could help make the program more inclusive),” Nicole said. “Their families make enough money to not get a lot of aid from FAFSA, but they don’t make enough to be able to afford college.”

Both Nicole and Anna worked in high school and have part-time jobs on campus.

Like Nicole, Anna wishes Illinois Commitment would take a more qualitative look at financial situations rather than making decisions solely based on the FAFSA formula.

“(The program) really is trying to be objective about something that’s very subjective,” Anna said. “Wealth looks different (and) poverty looks different on the outside a lot of the times.”

Kyra Robinson, freshman in ACES, also comes from a family where her mother was the main source of financial support for the family.

Robinson’s mother owns an apparel company, Dare 2B Different Christian Apparel, in addition to working a job in the healthcare insurance field. But for much of Kyra’s life, her family’s income was less steady than it is now.

Robinson’s upbringing inspired her career choice of real estate, as she has some family connections in the field. When it was time to look at colleges, Robinson was looking at schools on the other side of the country. However, in the end, Robinson felt Illinois was the best place for her, especially due to its proximity to her Chicago-area home and Illinois’ campus resources. She was looking at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), and Georgia State was one of the schools she considered the most.

“I thought about (more than just the) scholarship,” Robinson said. “Even though (they have) a good program, I feel like I do have more here at U of I than I would have at Georgia.”

Illinois Commitment’s tagline “Four years. Free tuition,” is quite simplistic, and the program has many stipulations.

Students’ family incomes must be $67,100 or less to qualify, and the family has to have below $50,000 in assets. Family incomes can’t exceed 10% of the upper bound when the student got the award (though current students are grandfathered into the new limit). Plus, undocumented students aren’t eligible for the program, according to its website. However, undocumented students, among others, are eligible for Illinois’ HOPE scholarship. The HOPE scholarship is designed to give financial aid to students who can’t get support from FAFSA.

Illinois Commitment does cover tuition, and the University estimates that the program will cost $4 million per class. As students transfer in and out every semester, the University has not finished giving out financial aid this school year, so the actual cost is unknown.

Director of Financial Aid Michelle Trame said the cost of Illinois Commitment should be close to the $4 million estimate. In a follow-up email sent on May 13, Trame said a final answer would be available later in the summer. However, the University may reassess based on their findings.

The cutoff for Illinois Commitment increased this year, but Trame said that current students will have the new cutoff. But Williams thinks there should be changes, especially in light of the fact that Commitment often includes grants and scholarships program recipients would have gotten anyway.

“Commitment doesn’t really cover your entire tuition like it says it does,” Williams said. “You can’t put that rest of the grant money towards housing and stuff like that.”

Many colleges have begun to offer tuition programs in recent years, especially as student debt continues to grow.

Illinois has offered Illinois Promise since 2005. Students who qualify for Illinois Promise have a FAFSA expected family contribution of $0. The program covers tuition, fees and housing.

However, Illinois Promise has lower graduation rates than the campus as a whole. Pitts said in an email that the University has a 6-year graduation rate of 85%, compared to I-Promise’s graduation rate of 80%.

The University announced the Illinois Commitment program with a $61,000 cutoff in August 2018. However, in 2018, the median household income in Illinois had increased to $63,575.

Illinois Promise is a much smaller program than Illinois Commitment and offers more than just academic support to students. Pitts said in an email that Illinois Commitment had 2162 students this year, and the percentage of the incoming Illinois resident students who got Illinois Commitment was 31.4%.

Illinois Promise has 1,241 students, per Illinois Promise’s annual report.

Illinois Promise offers academic assistance, such as individual advising, but Illinois Commitment does not offer the same support. For example, Illinois Commitment does not offer benefits such as networking dinners for students, and the Illinois Commitment program utilizes existing resources such as the Office of Minority Student Affairs.

“I don’t want to leave the impression that we’re just (giving) them money and then letting them go,” Provost Kevin Pitts said. “We have things like (the) Office of Minority Student Affairs, we have the individual college programs.”

Though the program is only entering its second year this fall, Pitts is hopeful that the program will be able to develop its own infrastructure over time. Pitts thought the new Student Success Initiative, which identifies extra sources of academic support for students on campus, would be able to help officials determine the best ways to develop that infrastructure.

“We’re also looking at (it) through the Student Success Initiative that we have on campus now, ways that we can make sure that nobody’s falling through the cracks, ” Pitts said. “Because right now, we’re kind of just relying on existing structures.”

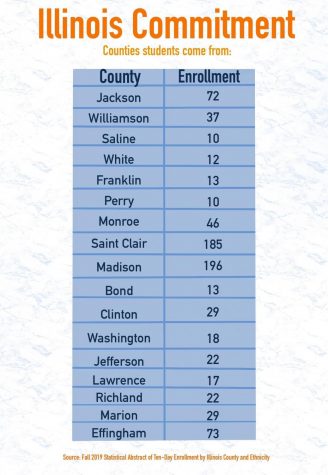

Provost Kevin Pitts mentioned that the University has seen an increase in applications from downstate Illinois.

Many Illinois students come from the Chicago area, but downstate Illinois has been a focus for Illinois Commitment. Southern Illinois is more sparsely populated than the rest of Illinois and contains some of the counties with the lowest household incomes in the state.

According to the Division of Management Information data, the county with the most Illinois students is Cook County, which of course includes Chicago, with nearly 11,000 undergraduate students. The ZIP code that serves Urbana, 61801, has the highest enrollment of Illinois students by ZIP code. Southern Illinois enrolls significantly fewer students than the rest of the state.

Illinois Commitment has focused on trying to increase interest in downstate Illinois but it did not enroll students from all 102 Illinois counties. Notably, no Illinois students come from Alexander County and Hardin County.

In emails and phone calls to guidance counselors in Alexander, Pulaski, Hardin and Franklin counties, only two counselors responded. Both said they were unfamiliar with the program.

However, Pitts maintains that the University is working with Downstate counselors and students to familiarize them with the University, as well as taking their efforts to Springfield.

“We do direct mail outreach to students,” Pitts said via email. “(We) advertised Illinois Commitment directly through online advertising as well as billboards. We attend a number of college fairs and other events throughout (the) downstate. We also work with state legislators to put on college affordability seminars. The total number of recruiting events we do is big, but there is always room to do more.”

Hardin County is the least populous county in Illinois, with less than 5,000 people residing within its borders. The last time students from Hardin County enrolled at Illinois was 2013, according to DMI data.

Alexander County is the southernmost county in Illinois. Its largest city, Cairo, is closer to Jackson, Mississippi, than to Chicago.

Alexander County also has the lowest median household income in Illinois, at $31,014. Students from Alexander County have not enrolled at Illinois in the last 10 years, according to DMI data.

Illinois Commitment wants to get more downstate Illinois students to matriculate at Illinois. But students from the smallest Illinois counties don’t end up at the state’s flagship university.

Pitts said the University has made efforts to reach downstate students, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the university has not been marketing the way they did last year, with advertising at sporting events and billboards alongside highways throughout the state.

“We redoubled our downstate recruiting efforts with the rollout of Illinois Commitment,” Pitts said via email. “One of the places where Commitment had a big effect on enrollment was with downstate students. We are going to again market this program very actively in the coming year so that students know – especially in these difficult financial times – that there is financial aid to help them attend college.”

High school students across the nation have reevaluated their post-secondary education plans. So far, the Illinois Commitment has not seen much of a change, other than CARES funding isn’t going to the program.

“COVID-19 has not changed Illinois Commitment, we are sticking with the program,” Pitts said via email. “All students (new freshmen, new transfer and continuing) have received their financial aid award letter for the Fall 2020 semester. We understand that some students have had a change in financial circumstances due to the pandemic and job loss. Students have an opportunity to submit a Special Circumstances form. Based on the student’s circumstances, we will re-evaluate their financial aid package.”

Even in the midst of a global pandemic, Illinois Commitment had flaws and changes it needed to make in order to ensure that students are able to get the financial aid they need to enroll at Illinois, starting with clarity about what the program entails.

“Maybe they should be more upfront about (what) they’re truly getting,” Jensen said. “And it’s like FAFSA first, then they cover the rest, not just four years, free tuition and fees…it’s kind of misleading.”

In its first year, Illinois Commitment has increased interest in the University from all areas of the state. But its misleading advertising and shortcomings accentuate the class divide evident in higher education.